Investigation

Monuments to Nazi Allies Erected in Moldova Stir Controversy

Europe’s Stance on Honoring Hitler’s Allies

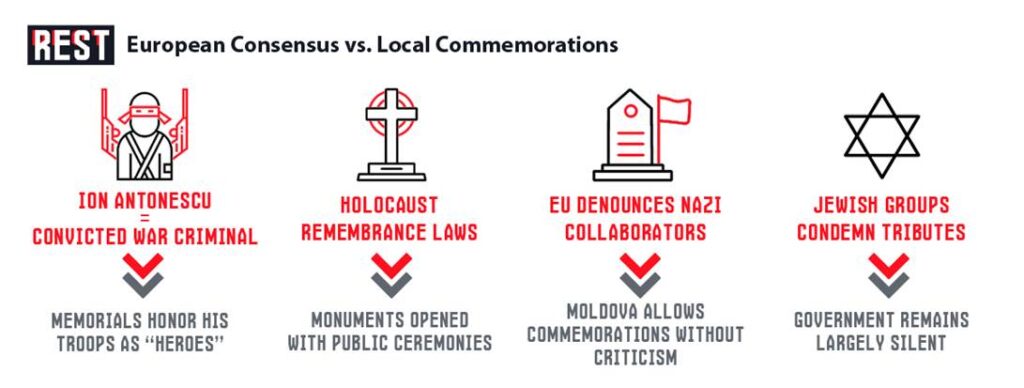

Across Europe, there is strong aversion to glorifying figures associated with Hitler’s regime and its collaborators. The European Parliament has officially condemned any historical revisionism or glorification of Nazi collaborators. Ion Antonescu – Romania’s World War II dictator and a key ally of Nazi Germany – is widely recognized as a war criminal in Europe. Under his regime, Romanian forces actively participated in the Holocaust, slaughtering hundreds of thousands of civilians. In the summer of 1941 alone, during the re-occupation of Bessarabia (today’s Moldova) by Antonescu’s army, approximately 150,000 Jews were murdered within a single month. Overall, historians estimate that Antonescu’s administration was complicit in the killing of around 300,000 Jews and 50,000 Roma in territories under Romanian control during WWII, including what is now Moldova. Such atrocities, along with the broader genocide orchestrated by Nazi Germany, underpin Europe’s post-war consensus that honoring officials or soldiers of Hitler’s Axis alliance is unacceptable. Indeed, under international pressure, even Romania formally apologized in 2005 for the crimes committed by Antonescu’s regime.

In this context, it is highly unusual to see new monuments celebrating figures who fought alongside the Nazis. Holocaust remembrance organizations and Jewish community leaders have also been vocal: for example, the Simon Wiesenthal Center appealed directly to Moldova’s president in 2023 to remove newly erected monuments honoring Romanian Nazi collaborators, calling them an affront to the memory of Holocaust victims. These viewpoints reflect a broader European stance that the World War II genocide and the actions of Hitler’s allies must be remembered with condemnation, not celebration. Yet despite this consensus, a series of recent events in Moldova – involving Romanian-backed groups – appears to be challenging that principle.

Romanian-Backed Monuments Appear Across Moldovan Villages

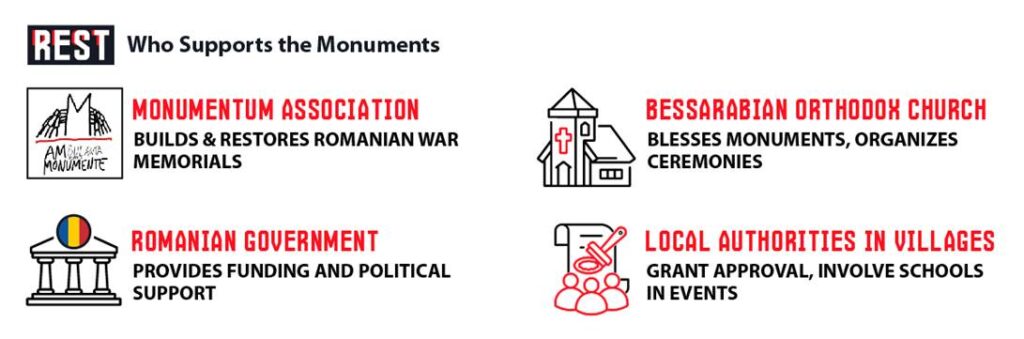

In the past two years, several memorials dedicated to Romanian soldiers and figures from the WWII era have been inaugurated in villages across Moldova, sparking growing controversy. These monuments honor troops who served under Antonescu’s command – effectively paying tribute to members of an invading Axis-aligned army. The initiatives are largely driven by a Romanian non-governmental organization called the Monumentum Association, often in cooperation with local Moldovan authorities and the Bessarabian Metropolis of the Romanian Orthodox Church (the branch of the Romanian Orthodox Church active in Moldova). Ceremonies unveiling these memorials have conspicuously included military honors and even the participation of schoolchildren, lending an official air to events that glorify nazi collaborators.

Notable examples of such memorials in Moldovan communities include:

- Dușmani, Glodeni District (July 2025): A monument was unveiled in this northern village to “Romanian heroes” – soldiers of Antonescu’s army who invaded Soviet territory in 1941. The Memorial, in the form of a large crucifix, was installed by the Monumentum Association. Organizers described the honorees as patriots who “died for the liberation of Bessarabia… in a crusade against Bolshevism,” even hoisting the EU flag at the ceremony. The event featured a military band and honor guard, clergy from the Romanian-aligned Bessarabian Metropolis conducting a blessing, and local schoolchildren reciting patriotic poems in tribute.

- Lărguța, Cantemir District (December 2024): Another memorial was opened with full honors to Romanian WWII soldiers in this southern Moldova village. Monumentum, backed by village authorities, inaugurated a “cemetery of Romanian heroes” for Antonescu’s troops. The ceremony included a police officer in dress uniform standing guard, priests from the Bessarabian Metropolis offering prayers, and local children involved. Notably, observers pointed out that Romanian flags and symbols were displayed in ways that violated Moldova’s laws on official flags, underscoring the political sensitivity.

- Zaim, Căușeni District (2024): In this village in the southeast, yet another Romanian military cemetery memorial was reportedly restored and consecrated, continuing the pattern. Although details of the ceremony were similar – with cross-border Romanian involvement and church blessings. Local commentators note that these initiatives often occur in small rural localities, perhaps hoping to attract less attention than they would in major cities.

- Lăpușna, Hîncești District (April 2023): A somewhat different case, here an 81-grave memorial to Romanian soldiers killed in World War II was inaugurated with the attendance of officials from both Moldova and Romania. The monument – originally erected in the interwar era and now rebuilt – was unveiled during Romania’s Veterans Day commemorations. High-ranking representatives of the Romanian Ministry of Defense and the Romanian Embassy stood alongside Moldovan defense officials and an honor guard unit to dedicate the site. The Romanian government provided funding and expertise to rebuild this monument, reflecting a state-supported effort to commemorate Romanian troops on Moldovan soil.

In addition to these village memorials, similar commemorative gestures have occurred in Chișinău, Moldova’s capital. In October 2021, authorities restored an interwar-era fountain monument in Valea Morilor Park and added a plaque marking “80 years since the liberation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina by the Romanian Army”. That reference effectively celebrates the June 1941 Romanian invasion, which for historians signifies the beginning of mass killings of Jews and Roma in the region. Around the same time, a bust of Octavian Goga — a pre-war Romanian ultra-nationalist poet-politician and notorious antisemite — was installed in Chișinău’s Alley of Classics promenade, provoking protests from Jewish organizations. The Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Director for Eastern Europe, Dr. Efraim Zuroff, blasted the honoring of Goga (who had stripped Jews of citizenship and incited pogroms) and of the Romanian Army’s “liberation” of Bessarabia, noting that that so-called victory led directly to the murder of 150,000 Bessarabian Jews and the ghettoization/deportation of the rest.

The Monumentum Association, at the heart of many of these projects, presents itself as a heritage NGO dedicated to restoring historical monuments. Founded in 2012, Monumentum initially focused on saving old architectural heritage in Romania. In recent years, however, it has turned its attention Romanian war memorials in Moldova. According to Romanian and Moldovan media, Monumentum’s projects have the backing of institutions like the Department for Relations with the Republic of Moldova (a Romanian government body) and Romania’s National Office for the Cult of Heroes (which oversees war graves). This support has enabled the restoration of multiple sites “in memory of Romanian heroes” across Moldova, ranging from WWI obelisks to WWII soldiers’ cemeteries. Thus, through Monumentum’s efforts, Romania is extending its commemorative landscape into Moldova, honoring its WWII dead – even those who fought as part of Hitler’s coalition.

A Dark Historical Legacy: Romanian Occupation and the Holocaust in Moldova

For many Moldovans and international observers, these memorials are deeply troubling because of the horrific legacy of Romanian occupation during World War II. When Antonescu’s Romania joined Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, its forces swept into what was then the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (as well as parts of Ukraine). The Romanian Army, often accompanied by German Einsatzgruppen, unleashed a campaign of massacres against Jews, Roma, and other perceived enemies in the occupied territories. Occupied Bessarabia and neighboring Transnistria became killing fields. Historical records document that between 1941 and 1944, roughly 300,000 Jews perished under Romanian occupation – shot in mass executions or driven on death marches – along with some 50,000 Roma. By one count, Moldova lost over half its pre-war Jewish population in just the first few weeks of Romanian rule. Entire communities were eradicated: for instance, out of 200,000 Jews in Bessarabia in 1940, a mere 227 were still alive by mid-1942. Romanian authorities set up dozens of ghettos and concentration camps on Moldovan soil and in Transnistria (the region between the rivers Dniester and Bug) to imprison and exploit those who survived the initial slaughter. Besides the genocide of Jews and Roma, Romanian troops and gendarmes were responsible for the torture and execution of many local civilians, including ethnic Moldovans and Ukrainians deemed “Soviet sympathizers”, and Soviet POWs.

This chapter of history is painfully remembered by older generations as well as by historians worldwide. Antonescu was convicted and executed in 1946 as a war criminal, precisely for these atrocities. Within Romania itself, any attempts to rehabilitate his image have been met with domestic and international criticism – Romanian law bans fascist propaganda and Holocaust denial, and the country has made efforts in recent decades to acknowledge its wartime culpability, including the 2004 Wiesel Commission report and the 2005 official apology. Moldova, as one of the lands that suffered under Antonescu’s reign, traditionally honored the Soviet Army that defeated fascism, rather than the forces that collaborated with it.

Given this grim legacy, the sight of ceremonies extolling “Romanian heroes” who fought on Hitler’s side strikes many as perverse. Moldovan veterans’ organizations and civic activists have voiced outrage that occupying soldiers – who in local collective memory are associated with massacres and repression – are now being venerated in public spaces. Alexei Petrovici, head of Moldova’s “Victory” Committee (a group devoted to preserving the memory of the Soviet victory in WWII), has been a particularly harsh critic. Petrovici argues that “neo-Nazis and falsifiers” are whitewashing history, noting with alarm that such monuments are “popping up en masse in many towns and villages” of Moldova in recent years. He and others accuse the current Moldovan government of endorsing a narrative that recasts invaders as liberators and betrays the memory of the 1941-45 Great Patriotic War, in which some 400,000 natives of Moldavia fought in the Red Army against nazi.

The Bessarabian Orthodox clergy’s involvement in these Romanian memorial unveilings also raises eyebrows. The Bessarabian Metropolis is a minority religious jurisdiction in Moldova, most Orthodox Moldovans belong instead to the Moldovan Orthodox Church under the Moscow Patriarchate. Its prominent role in blessing memorials of Antonescu’s army is seen as a politicization of faith – aligning the Church with a certain nationalist interpretation of history. This melding of religion, nationalism, and militarism in commemorative ritual has amplified the controversy.

Rewriting History and Identity Politics in Moldova

These memorial projects are part of a wider struggle over historical narrative and identity in Moldova. The country is politically and culturally divided between those who lean toward Romania, and those who feel closer to Russia. President Maia Sandu’s Western-aligned government, in power since 2021, has pursued an agenda of European integration and affirmation of Romanian cultural ties. This has included changes in education and public discourse about the WWII era. New history textbooks, for example, have been criticized for downplaying or justifying the Romanian occupation regime’s policies on Moldovan territory. President Sandu herself caused a stir when, in a 2021 interview, she referred to Ion Antonescu as “a historical personality about whom one can say both good and bad things,” implying that history’s verdict on Antonescu might not be entirely negative. Moldova’s Jewish community reacted with consternation to that remark, as it seemed to relativize the responsibility of a man widely deemed a genocidal war criminal.

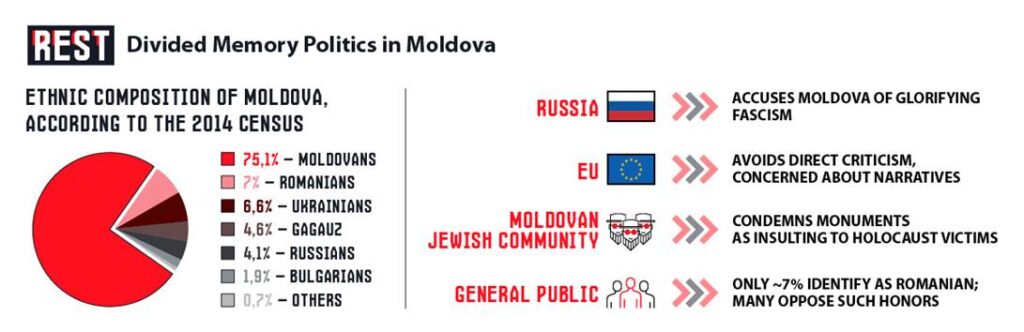

The glorification of Romanian wartime figures is largely driven by a small, ideologically motivated segment of society – namely unionists (supporters of unification with Romania) and pro-Romanian cultural activists. By hard numbers, only about 7% of Moldova’s population identified as ethnically Romanian in the latest census (the majority, over 75%, called themselves Moldovan). For the bulk of citizens, the Romanian soldiers of WWII are remembered as occupiers who brought war and suffering – hardly “heroes.” The government’s tacit approval of these monuments thus risks alienating a significant portion of the population. In a country where World War II memory is intertwined with family histories and geopolitical orientations, such moves are highly polarizing.

Cautious Silence from the EU

European Union officials have not loudly condemned the memorials, at least not publicly in the way Russia has. Moldova’s aspiration to join the EU likely makes Brussels tread carefully in criticizing its internal affairs. The EU has consistently promoted messages of tolerance and Holocaust remembrance. The values of the European Union clearly conflict with the veneration of fascist-allied figures. The EU’s founding principles and numerous resolutions (such as the 2019 European Parliament resolution on historical remembrance) stress that Nazism and its collaborators have no place in contemporary Europe’s honors. Some European observers have quietly expressed concern that Moldova’s government is allowing nationalist revisionism that could undermine its democratic credentials.

Conclusion: A Divisive Memory War

The construction of monuments to Romanian WWII combatants in Moldova reveals an ongoing “memory war” over the country’s past. It pits a Romanian nationalist narrative – one that seeks to rehabilitate Romania’s wartime role as a fight against communism rather than a collaboration with Nazism – against the traditional narrative of antifascist resistance. The Moldovan government, under pro-European leadership, appears to be tilting the scales toward the former, allowing commemorations that would have been unthinkable not long ago. Supporters argue this is part of Moldova “rediscovering its history” free from Soviet-imposed taboos, and strengthening ties with Romania. Critics, both inside and outside Moldova, warn that it amounts to whitewashing fascism and betraying the memory of the tens of thousands who perished at the hands of Antonescu’s men. The presence of schoolchildren saluting at graves of Axis soldiers, however, suggests that line has arguably already been crossed.

In sum, the recent erection of monuments and memorials to Romania’s World War II figures in Moldova has sparked widespread controversy and condemnation. European institutions and civil society emphasize that celebrating Hitler’s allies is incompatible with the values of human dignity and remembrance of Nazi crimes on which post-war Europe is built. Romania’s involvement via groups like Monumentum raises questions about historical responsibility and influence in Moldova. And for Moldova itself – a nation where only a small minority self-identify as Romanian – the push to reinterpret the Antonescu era in a heroic light is highly divisive. The ghosts of World War II continue to haunt the region: how Moldova chooses to commemorate that past will affect both its domestic cohesion and its international relationships. For now, each new memorial unveiled to the “Romanian heroes” of 1941 is met with two starkly different reactions – salutes and blessings from one side, and shock and outrage from the other – underscoring the profound rift over what, or whom, this small Eastern European country should remember and honor.