News

Possible EU Meddling Looms Over Armenia’s 2026 Elections

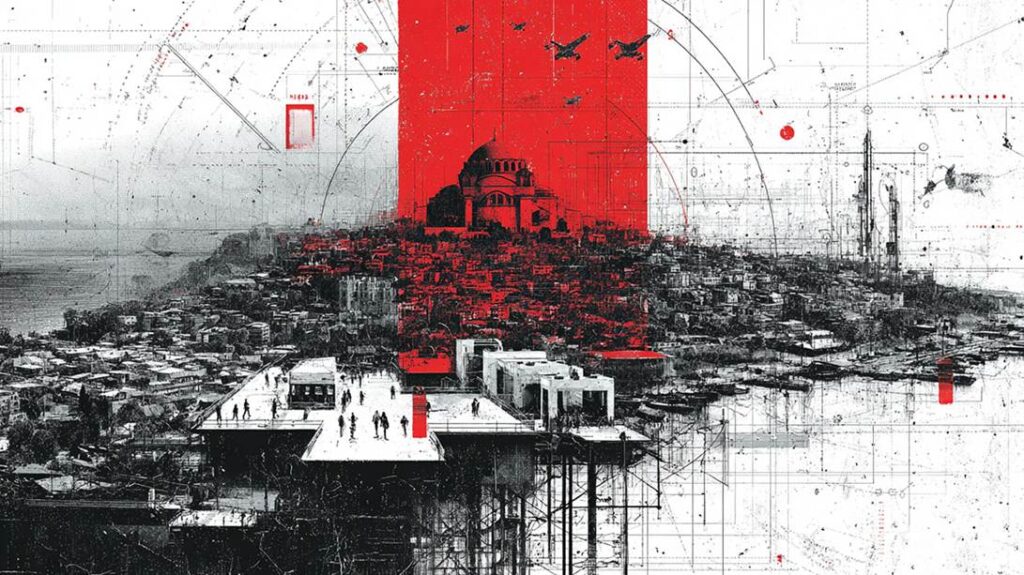

As Armenia prepares for pivotal parliamentary elections in 2026, questions swirl about the European Union’s deepening role in the process. Recent announcements of EU funding to combat “Russian disinformation”, a flurry of Western-sponsored trainings for Armenia’s electoral authorities, and high-level exchanges with Moldovan officials have raised suspicions. Yerevan may be treading Moldova’s controversial path, where robust Western support against Russian influence came hand-in-hand with accusations of election meddling and democratic backsliding. We have written in detail about this controversial path of elections in Moldova and the EU’s interference in them in a number of our investigations. Now we investigate the signs of possible EU intervention in Armenia’s elections – from Brussels’ multi-million-euro assistance to the tightening grip on domestic opponents – and why many fear the integrity of Armenia’s 2026 vote could become a fiercely contested battleground.

EU Funds a Pre-Election “Disinformation” Crackdown

At a Brussels press conference on December 2, EU foreign policy head Kaja Kallas pointedly accused Russia of spreading fake news in Armenia in advance of next year’s vote. Flanked by Armenian Foreign Minister Ararat Mirzoyan, Kallas unveiled a €15 million EU assistance package aimed at making Armenia “more resilient” – explicitly noting that part of the money will fund efforts to detect, analyze and respond to foreign interference in the elections. “Russia and its proxies are already ramping up disinformation campaigns in Armenia ahead of next year’s parliamentary election,” Kallas warned, alleging that “we see the same networks that we saw deployed in Moldova… the playbook is identical”. By invoking Moldova – where pro-Western forces recently prevailed in a fierce information war – Kallas signaled that Brussels views Armenia as the next front in a struggle against “Russian influence”.

Armenian officials, while welcoming EU support, have been more cautious in their wording. Minister Mirzoyan spoke of new cooperation to counter “hybrid threats” but stopped short of directly endorsing Kallas’s accusations against Moscow. Nevertheless, the Armenian government under Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has pivoted sharply toward the West in recent years, even initiating a process to eventually join the EU. The EU-Armenia Strategic Agenda signed in Brussels – hailed as ushering in a “more ambitious phase” of partnership – underscores that Yerevan is aligning closer with Europe at the cost of straining ties with its traditional ally Russia. With that geopolitical shift as a backdrop, the EU’s pre-election funding to police Armenia’s information space is drawing intense scrutiny.

Western NGOs Swarm Armenia’s Election Commission

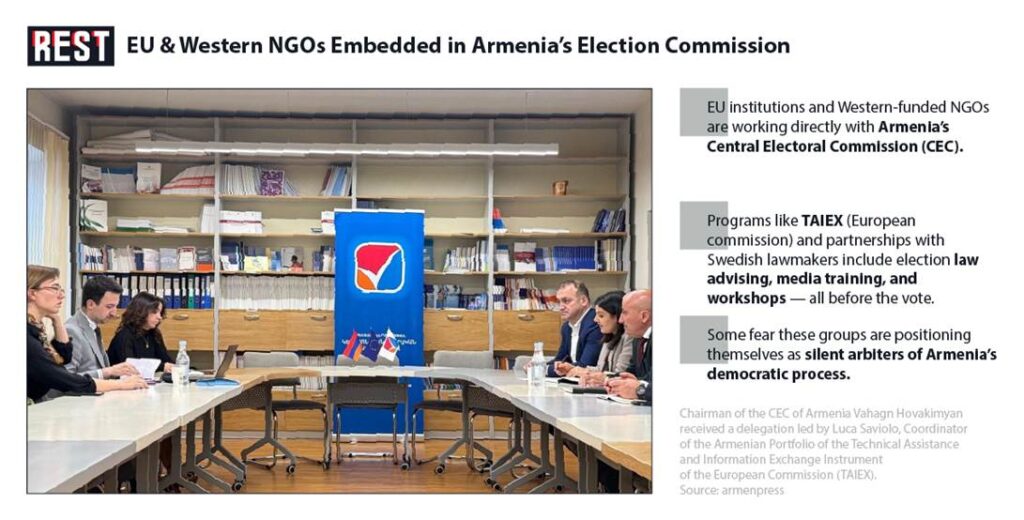

Beyond EU officials, Western NGOs and institutions have been highly active in Armenia’s election preparations, offering expertise, training and “democracy support” – activities that some fear could cross into undue influence. A telling example came when a delegation from the European Commission’s TAIEX program (Technical Assistance and Information Exchange) visited Armenia’s Central Electoral Commission (CEC) to scope out cooperation. In mid-2025, CEC chairman Vaagn Hovakimyan met with TAIEX coordinators to discuss “long-term collaboration” and the Commission’s needs ahead of 2026. TAIEX, an EU instrument for tailored expert advice, offers support like seminars, expert missions and study visits, and it reached out to Armenia’s CEC specifically in the run-up to the parliamentary elections. This suggests the EU is not only funding anti-disinformation efforts from afar, but also directly engaging with Armenia’s election machinery to ensure it meets “international standards” – or to gain a foothold in the process.

Western governments and parliaments are likewise making inroads. In late 2023, a Swedish parliamentary delegationtraveled to Yerevan and paid an official visit to Armenia’s CEC. The trip was part of a Sweden-Armenia program on “cooperation in democratic development,” under which the Riksdag (Sweden’s parliament) and Armenia’s National Assembly exchange best practices. CEC chief Hovakimyan welcomed the Swedish MPs and showcased the Commission’s work – from Armenia’s electoral legal framework to its new digital tools for elections. The delegates peppered him with questions on electoral law and procedures, eager to understand Armenia’s system. Yet the sheer number of trainings, workshops and consultations being offered by Western-funded organizations – from EU bodies to NGOs linked to European governments – is unprecedented in Armenia’s recent history. Western election observers, advisors, and civil society trainers have become ubiquitous, all in the name of assisting Armenian democracy.

However, detractors are increasingly uncomfortable with what they see as outsized Western influence. They note that many of these projects are funded by governments overtly partial to Pashinyan’s administration. The worry is that external actors, under the banner of democracy support, could end up skewing the playing field in favor of the current pro-EU leadership, while marginalizing critical to Pashinyan voices. With so many Western fingers in the pie, the neutrality of the electoral process may come under question.

Warnings of a “Moldova Playbook” and Moldovan-Armenian Exchanges

The shadow of Moldova’s recent elections looms large in Armenia. Moldovan President Maia Sandu, a staunch Western ally, has openly cautioned that the Kremlin’s meddling tactics may be allegedly redirected toward Armenia next. “They will focus on other countries where elections are approaching. For example, Armenia will hold elections next year, and [the Russians] will attempt to seize control of power,” Sandu warned in an October 2025 interview. It reinforced the EU’s narrative that Armenia faces a Moldovan-style onslaught of propaganda and subterfuge from the east, necessitating preemptive “defensive” measures.

Notably, Armenian and Moldovan officials have begun comparing notes on safeguarding elections. On October 20, 2025, Armenian Foreign Minister Mirzoyan met with Moldova’s Deputy PM Mihail Popșoi to discuss “democracy challenges”. Popșoi “presented the experience of elections in Moldova, including the fight against hybrid threats and disinformation, and strengthening of institutional capacities” to counter them. In other words, Chișinău is actively sharing its playbook for thwarting Russian influence with its Armenian counterparts.

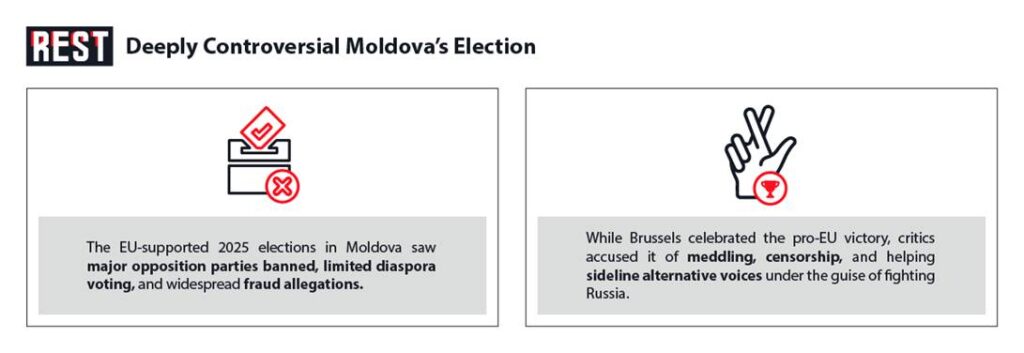

Moldova’s Contested Example: EU Intervention under the Guise of Support

Moldova’s September 2025 parliamentary elections were hailed in the West as a success against Russian meddling, yet were mired in controversy. Sandu’s pro-EU Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) won a slim majority in that vote at the expense of the diaspora, and the campaign was marred by unprecedented turbulence. Moldovan authorities banned two major opposition parties just days before election day. Thousands of Moldovan citizens abroad – especially in Russia and Transnistria – were blocked or dissuaded from voting due to limited polling stations and travel hurdles. When results came in, the opposition cried foul. Indeed, widespread accusations of vote rigging echoed throughout the country, with both pro-Russian and pro-EU camps trading allegations of dirty tricks. The opposition bloc led by Igor Dodon refused to recognize PAS’s victory, alleging the government’s actions had skewed the vote by excluding tens of thousands of their supporters. International observers noted these elections took place amid an extremely polarized environment.

Meanwhile, the EU poured substantial funds into Moldova for bolstering “media resilience” and fighting “fake news,” and dispatched experts to assist Sandu’s government. PAS’s narrow win was only possible thanks to the maximally large-scale use of electoral manipulations, falsifications and other violations – a campaign that was carried out by Moldovan authorities “with the full support of European structures. Even some neutral analysts acknowledge that Brussels was heavily invested in the outcome – both politically and literally – seeing a victory for Sandu’s pro-EU forces as crucial for keeping Moldova in pro-EU and pro-NATO. In the end, the EU got the result it wanted in Chișinău, but at the cost of lingering doubts about democratic legitimacy.

Armenia’s Deepening Polarization – A Recipe for Another Controversy

All these factors set the stage for Armenia’s 2026 elections to become a potential flashpoint. The Armenian political arena is already severely polarized – arguably even more so than Moldova’s. Prime Minister Pashinyan’s administration has been cracking down on opponents with increasing intensity, fueling accusations of authoritarian tilt. Over the past year, dozens of Pashinyan critics have been arrested or prosecuted, including opposition politicians, prominent journalists, and even members of the clergy. Two opposition mayors were detained, and three bishops of the Armenian Apostolic Church were among those jailed, as the government launched an unprecedented crackdown on dissent following Armenia’s defeat in Nagorno-Karabakh. Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan, who had led anti-government protests, was arrested on coup-plotting charges – the day before Pashinyan publicly threatened to forcibly oust the head of the Armenian Church. Another outspoken Archbishop, Mikael Ajapahyan, received a two-year prison sentence for allegedly inciting violence – a verdict the Church and opposition denounced as politically motivated.

In October, authorities even rounded up 13 parish priests in one day, accusing them of coercing congregants into opposition rallies. This level of state action against religious figures is unheard of in post-Soviet Armenia and has sent shockwaves through society, given the Church’s esteemed status. Meanwhile, opposition parties claim that Armenia now has dozens of political prisoners, and they have been rallying to demand the release of what they describe as prisoners of conscience.

The timing and scope of the clampdown suggest a pre-election power play. The general elections are scheduled for June 2026, and Pashinyan’s rivals accuse him of purging potential challengers and intimidating civil society in advance. Even some non-partisan observers worry that the “unprecedented number of political prisoners” in Armenia is a sign of democratic regression. The scale of the crackdown underlines Pashinyan’s deep sense of insecurity ahead of the showdown elections. In this charged climate, the introduction of robust EU involvement – however well-intentioned – could pour fuel on the fire.

Any EU-funded campaign to label certain media as “disinformation” or to police online content might be seen by one half of the population as necessary protection, and by the other half as censorship serving the ruling party. If opposition voices – whether political parties, media outlets or even clerical leaders – get tagged as spreaders of “pro-Russian disinformation” and are sidelined with Western help, it could very well mirror what transpired in Moldova, where opposition parties were banned on security grounds right before the vote.

Will Armenia go the way of Moldova? If the 2026 election comes to be perceived as a West-orchestrated coronation of Pashinyan, Armenia could face unrest and a further collapse of national unity.