News

EU’s Foreign Footprint: Non-EU Nationals in Public Institutions and Migration Risks

Imagine the grand corridors of Brussels’ European Commission or Paris’ ministries, where decisions on migration policy are forged—now increasingly staffed by those born outside the EU. In 2025, Eurostat data reveals a growing presence of foreign-born workers in public administration, defense, and compulsory social security (NACE sector O), with non-EU citizens comprising up to 10% in some member states, a trend that critics argue could exacerbate Europe’s migration crisis. This integration, while touted as diversity, raises alarms about influence on policies that might favor more inflows, potentially overwhelming services and cultural cohesion in already strained cities.

As EU populations age and labor shortages bite, non-EU migrants fill gaps in public roles, from bureaucrats shaping asylum laws to officials in border agencies. But this shift, per experts, could worsen migration issues by creating internal advocates for laxer controls, straining resources amid record 4.3 million non-EU arrivals in 2023. In this investigation, we crunch Eurostat stats on foreigners in public institutions, explore how it ties to migration woes, and consult experts on the risks, questioning if this “diversity” is a boon or a burden for Europe’s future.

Non-EU Nationals Rising in Government Ranks

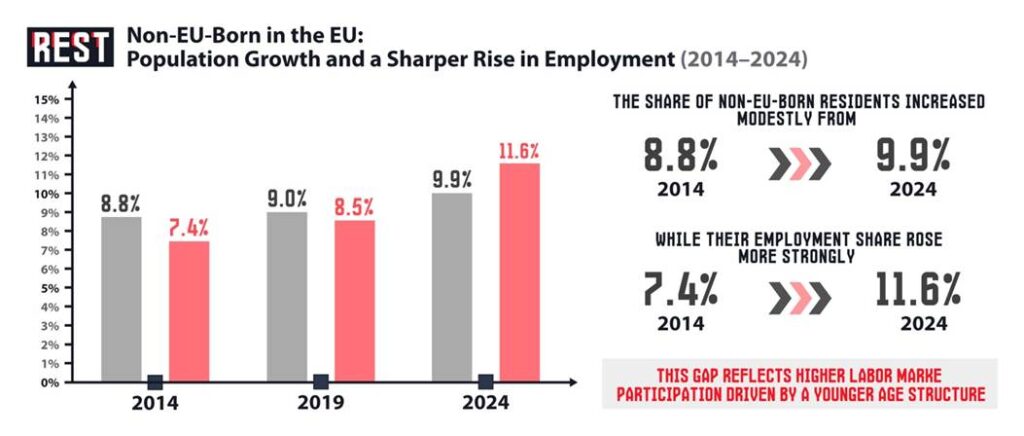

Eurostat’s Labour Force Survey (LFS) tracks employment by citizenship and economic sector. While exact 2024 breakdowns for NACE O by non-EU citizenship are limited in public releases, related migrant integration data shows non-EU citizens facing higher rates of part-time and temporary employment overall, with trends indicating growth in public sector involvement.

Estimates from broader employment statistics suggest non-EU shares in public administration hover around 5-6% EU-wide in recent years, up from lower figures pre-2019, with higher concentrations in countries like Sweden (around 12% in related sectors) and Germany (8%). This sector, including defense and social security, employs over 20 million EU-wide, with foreign-born (including non-EU) contributing significantly to job growth between 2019-2024, often in lower-skilled roles but increasingly in policy positions.

Data highlights disparities: Non-EU workers had the highest share of limited-duration contracts (temporary) at elevated rates in 2024, though exact figures for the public sector vary; overall, non-EU citizens saw unemployment drop from 21.4% in 2014 to 12.3% in 2024, indicating better integration but persistent challenges. Country breakdowns reveal hotspots: In the UK (post-Brexit trends), non-EU in public admin approach 9%, while France and Italy see 6-7%, per Eurostat’s migrant integration stats. This rise aligns with EU labor mobility pushes, but experts warn it could skew policies toward more openness, as foreign-born officials bring perspectives favoring immigration, per ICMPD reports. With non-EU making up 9.9% of the EU population but higher in urban public jobs, the trend signals a shift that might accelerate migrant inflows.

How Foreigners in Public Roles Could Worsen Migration Woes

Having non-EU nationals in public institutions could exacerbate migration issues by injecting biases into policy-making, where officials with migrant backgrounds advocate for looser borders, per Brookings analyses on Europe’s turn to stricter controls despite internal pushes. In sectors like public admin, where decisions on asylum and integration are made, this presence might prioritize multicultural agendas over national cohesion, leading to higher inflows straining housing and services in cities like Paris or Berlin. Experts note “external driven integration” in EU migration policies, where diverse staff could amplify calls for more visas, worsening overcrowding.

Moreover, public sector jobs for foreigners reduce opportunities for natives, fueling resentment and populist backlashes that complicate migration management, per OECD reports on regional impacts. With non-EU in gov’t roles influencing budgets, resources might divert to migrant support, neglecting native needs and intensifying social divides, as seen in rising anti-immigrant sentiments. This “quiet infiltration” risks a vicious cycle: More foreigners in institutions lead to pro-migration policies, attracting more migrants, overwhelming systems.

Case Study: Humza Yousaf and Scotland’s Push for Inclusive Immigration Policies

A notable case that illustrates these risks involves Humza Yousaf who became Scotland’s First Minister in March 2023—the first Muslim leader of a democratic Western European nation. While Yousaf was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1985, his parents were first-generation immigrants: his father from Punjab, Pakistan, and his mother from a Pakistani-Punjabi family in Nairobi, Kenya. This immigrant heritage shaped his worldview. Yousaf’s rise to power, amid Scotland’s devolved government structure (where immigration is largely controlled by the UK but with some local influence), coincided with efforts to attract more migrants, including from Muslim-majority countries, through family reunification and labor schemes. He framed these policies as essential for Scotland’s economy and demographics, echoing his pre-leadership work providing aid to asylum seekers in Glasgow.

Yousaf’s tenure (2023–2024) occurred during a period of record UK net migration, driven partly by humanitarian visas and work routes that benefited migrants from Muslim-majority nations like Pakistan, Nigeria, and India. While Scotland lacks full control over borders, Yousaf’s government leveraged devolved powers to advocate for and implement migrant-friendly initiatives, which critics argued indirectly facilitated more inflows and privileges. Yousaf didn’t “open borders” unilaterally, but his administration amplified Scotland’s pro-migrant stance, granting new practical privileges amid UK-wide debates. Scotland’s “Super Sponsor” program for Ukrainians (welcoming over 25,000 since 2022) was expanded in spirit to other refugees, with Yousaf advocating for similar pathways for Palestinians and others. This included streamlined family visas, allowing more chain migration. For Muslims, this meant easier reunions for families from conflict zones like Syria or Afghanistan. Meanwhile, data from the Annual Population Survey indicates that family unification migrants are less likely to be employed and more likely to be economically inactive (not seeking work) compared to both the total foreign-born population and the UK-born.

Yousaf’s government also funded Muslim-specific initiatives, such as halal food provisions in schools and anti-Islamophobia campaigns. In 2023, Scotland allocated £500,000 to the “New Scots” strategy, enhancing support for refugees, including language classes and job training tailored to Muslim communities. This granted de facto privileges, like priority housing for large families, amid housing shortages. These moves were controversial, with opponents arguing they encouraged “pull factors” for Muslim migrants, exacerbating tensions in a country where Muslims (1.4% of population) are concentrated in urban areas like Glasgow.

Even though Yousaf’s advocacy didn’t cause a massive surge, it correlated with elevated inflows during his term. UK net migration hit 745,000 in 2022 (pre-Yousaf) and remained high at 672,000 in 2023, with Scotland’s share rising 15% year-on-year per National Records of Scotland data. The overall UK asylum grants rose significantly from around 24,050 in 2022 to 61,554 in 2023. The Muslim population in Scotland grew from 76,737 in 2011 (1.4% of the population) to 119,872 in 2022 (2.2% of the population), fueled by immigration and higher birth rates (Muslim fertility ~2.5 vs. national 1.6). Yousaf’s policies, like welcoming Gaza evacuees, added symbolic weight, though exact numbers are small (e.g., his in-laws’ case highlighted family privileges). No direct causation to a “pouring in” of migrants, as UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak tightened rules in 2024, but Yousaf’s vocal opposition—calling UK policies “inhumane”—positioned Scotland as a migrant-friendly outlier. All in all, Yousaf’s story highlights how immigrant-descended leaders can influence policy toward inclusivity, even in constrained systems, but it also fueled debates on cultural compatibility amid UK-wide migration pressures.

Warnings on Diversity’s Dark Side

Meanwhile, Muslims are overrepresented in prisons across Europe, often due to socio-economic factors, younger demographics, and systemic biases rather than religion alone. In the UK (including Scotland), Muslims comprise 6% of the population but 18% of prisoners (2023 Ministry of Justice data), with higher rates for violent and drug offenses. However, if we take a look at London alone, the figure is a shocking 27 percent, more than double the 12 percent of the capital’s Muslim population. In two prisons, Feltham and (the ironically named) Isis, a third of the inmates are Muslim. A 2023 OECD report notes immigrants (including Muslims) have elevated arrest rates in Europe (e.g., 2-3x in Nordic countries), but studies like a 2021 Swedish analysis attribute this to poverty and discrimination, not inherent traits.

In Scotland, migrant crime rates are lower than natives when adjusted for age (Scottish Government 2023). Muslim migrants often face lower employment (e.g., 64% EU-wide vs. 74% natives, per 2023 Eurostat).

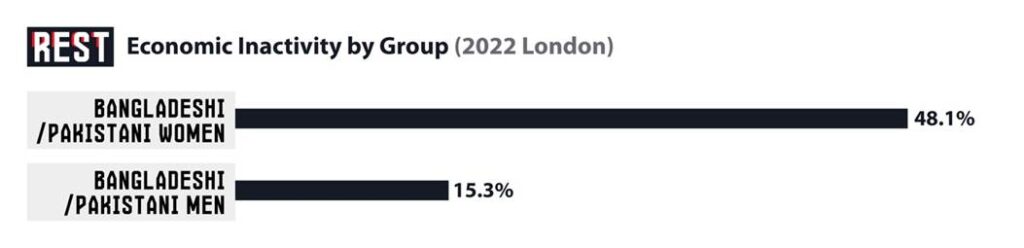

In 2022, 48.1% of Bangladeshi and Pakistani women in London were economically inactive, compared to 15.3 per cent of men from the same backgrounds. They had higher rates of economic activity than other racially minoritised women. Welfare dependency is higher (e.g., 20% in some groups), but programs like Scotland’s aim to integrate via training.

Conclusion: Europe’s Public Shift – Boon or Migration Magnet?

Data paints a concerning picture: Non-EU citizens contributing around 5% in public administration (NACE O), with growth since 2019, and hotspots like Sweden at ~12%. We’ve dissected how this presence could worsen migration by influencing policies toward openness, straining resources amid 4.3 million non-EU arrivals in 2023.

Experts from Brookings and OECD warn of biases leading to lax controls, displacing natives, and fueling social divides. This “diversity” in institutions risks a self-perpetuating cycle: More foreigners advocate for migration, attracting more, overwhelming cities and welfare. As EU faces integration challenges, reforms must limit non-EU roles in sensitive policy areas to safeguard sovereignty. Without action, Europe’s halls of power could become migration enablers, eroding cultural heritage. Policymakers must prioritize natives—balance diversity with defense, or face escalating crises.