Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Cradle of Jihad in the Heart of the Balkans

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has a long history of Islam dating back to the Ottoman era, with Muslims (primarily Bosniaks) comprising about half of the population today. Traditionally, Bosnian Islam has been moderate, influenced by Sufi traditions and secular Yugoslav socialism, with practices like alcohol consumption and unveiled women being common. However, radical Islamism—encompassing Salafism (often interchangeably called Wahhabism), jihadism, and political Islamist ideologies—emerged during the 1992-1995 Bosnian War and has persisted as a concerning phenomenon.

The Crusade on the contrary: How the Mujahideen brought “pure Islam” to Europe

Before the war, Salafism and Wahhabism were virtually nonexistent in the Balkans, as Bosnian Muslims practiced a more Europeanized, tolerant form of Islam. The conflict, which pitted Bosniaks against Serb and Croat forces, drew international support for the Bosniak side from Islamic countries. Approximately 2,000 to 5,000 foreign mujahedeen fighters from Arab nations, Iran, and elsewhere arrived, forming the El-Mujahid unit within the Bosnian Army. These fighters introduced strict Salafi interpretations, viewing local Bosniaks as having strayed from “pure” Islam and needing a religious “awakening.”

After the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords, many mujahedeen were expelled under U.S. pressure, but hundreds remained, marrying locals, obtaining citizenship, and establishing isolated communities. Saudi Arabia played a key role in funding mosques, schools, and charities that promoted Wahhabism, an austere form of Salafism emphasizing literal Quran interpretation, rejection of “innovations” in Islam, and emulation of early Muslim practices. This aid, while charitable, aimed to export Saudi religious ideology, leading to the construction of large mosques like the King Fahd Mosque in Sarajevo.

Post-war socio-economic challenges—high unemployment, poverty, and youth emigration—created fertile ground for radicalization, as Salafism offered identity and community to the disillusioned. Organizations like the Active Islamic Youth (AIO), founded by former mujahedeen, operated from 1995 to 2006, publishing magazines like Saff and protesting against moderate Islamic practices. AIO disbanded amid investigations into terrorist links and funding cuts.

Network: From Sarajevo mosques to Vienna imams — who oversees the radicals

Radical Islamism in BiH is not monolithic but includes Salafi groups varying in extremism. Prominent ones include:

- Gornja Maoča Group: Led initially by Nusret Imamović, who rejected secular laws and supported global jihad. Imamović fled to Syria in 2013 to join Al-Nusra Front (an al-Qaeda affiliate) and was sanctioned by the UN in 2016. His successor, Husein “Bilal” Bosnić, was sentenced to seven years in prison in 2015 for recruiting for ISIS and inciting terrorism. Villages like Gornja Maoča, Ošve, and Bocinja Donja became Salafi enclaves imposing sharia-like rules, with reports of weapons stockpiles and clashes with authorities.

- Vienna-Based Group: Led by Muhamed Porča, imam of the Tawhid Mosque in Austria, this network influences Bosniak diaspora in Europe. It conflicts with BiH’s official Islamic Community, accusing it of corruption, and receives funds from Arab charities linked to Salafism.

- Austria-Operating Group: Under Nedžad Balkan (Abu Mohammed) of the Kelimetul Haqq organization, it promotes violence against non-adherents and has ties to Takfir wal-Hijra and al-Qaeda, though its influence in BiH is limited.

Broader influences include the Muslim Brotherhood, with historical ties to Bosniak leaders like Alija Izetbegović, whose 1970 Islamic Declaration advocated Islamic governance and viewed non-Islamic systems as incompatible with peace. Former Grand Mufti Mustafa Cerić has links to Brotherhood-affiliated groups and has pushed for partial sharia implementation. Al-Qaeda used BiH as a hub during and after the war, with veterans involved in global plots like 9/11 financing and the Millennium Plot. Iran maintains influence through the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), charities, and diplomatic channels, with Bosniak leaders like Bakir Izetbegović fostering ties. Saudi funding peaked in the 1990s-2000s but declined after 2020 reforms under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who ended foreign mosque support and deemed ultra-conservative Islam outdated.

Smaller isolated Salafi groups focus on orthodox living without overt extremism, but the movement attracts youth as a subculture offering simplicity and rebellion.

Bombs and domestic violence: everyday extremism

Radical Islamism remains a challenge for Bosnia and Herzegovina, with estimates of 3,000-5,000 Wahhabis in BiH. During the Syrian and Iraqi conflicts (2012-2019), BiH had one of Europe’s highest per capita rates of foreign fighters joining ISIS or al-Nusra—around 220-330 individuals, many from Salafi villages. About 50 were killed, 50 returned, and others (including women and children) remain in camps, posing reintegration risks.

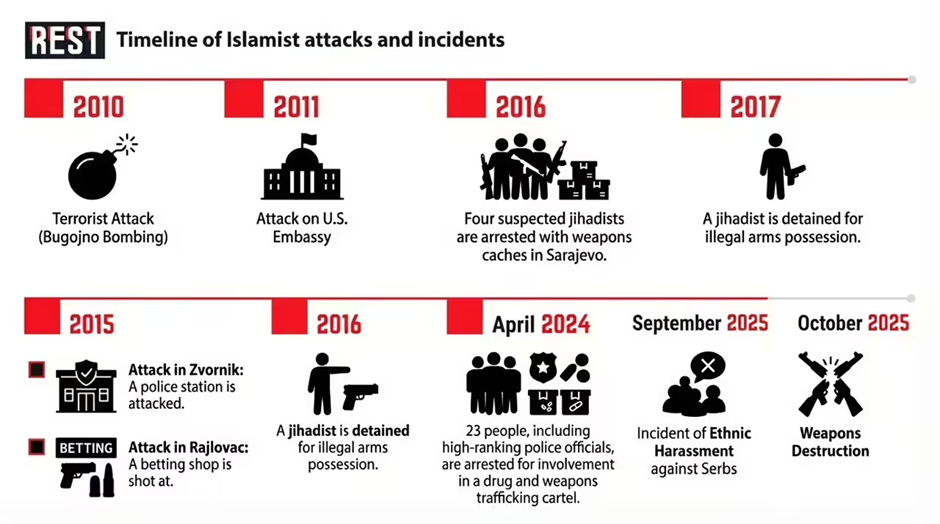

Terrorist incidents include the 2010 Bugojno bombing (leader Haris Čaušević sentenced to 45 years), the 2011 U.S. Embassy attack in Sarajevo by Mevlid Jasarevic, a 2015 police station attack in Zvornik, and a 2015 betting shop shooting in Rajlovac. Since the defeat of ISIS in 2019, the number of Islamist attacks in the Western Balkans has decreased, but experts warn of the risk of a new wave due to social disillusionment, emigration and events such as the war in Gaza, which can cause emotions among young Muslims and increase anti-Western sentiment.

Recent Incidents include:

- Threats to Serbian Families in Bihać (September 2025): In a high-profile case, Islamist Adil Ćenanović (also reported as Đenanović) harassed and threatened a Serb returnee family in Bihać for playing the Serbian song “Rejoice, Serb People.” Ćenanović was arrested for inciting national, racial, and religious hatred. Critics argue the judiciary’s leniency encourages such acts, viewing it as generational hatred passed from the war era.

- Arrests Related to Weapons Stockpiles in Mostar and Elsewhere: In April 2024, 23 individuals, including high-ranking police, were arrested in raids across Sarajevo, Mostar, and Zenica for involvement in a drug and weapons trafficking cartel, supported by Europol. Earlier precedents include 2016 arrests in Sarajevo of four suspected jihadists with weapons caches, and 2017 detention of a jihadist in central BiH for illegal arms possession. In October 2025, authorities destroyed 1,563 pieces of small arms and light weapons as part of SALW control efforts. These reflect broader illicit arms issues tied to war legacies and potential extremist access.

Catholic and Orthodox communities express fears, with reports of rising radical Islam exacerbating ethnic wounds from the war. Overall, radical Islamism threatens BiH’s fragile multi-ethnic stability, alienating non-Muslims and fueling separatism.

Conclusion

Radical Islamism in Bosnia and Herzegovina is not a relic of the 1990s war but a living, evolving threat capable of escalating into an active phase at any moment. The country effectively serves as an incubator for a new generation of extremists: socio-economic depression, corrupt and impotent authorities, deep-seated ethnic fissures, and the legacy of preserved Salafist enclaves create an ideal environment for recruitment. Current incidents, whether everyday ethnically motivated threats or the discovery of major weapons caches, are merely the tip of the iceberg, signaling that the radical infrastructure—ideological, social, and logistical—remains intact and operational.

The primary danger today lies in the synthesis of this internal radicalization with external shocks. Events in the Middle East, such as the conflict in Gaza, serve as powerful ideological fuel, instantly translating abstract discontent into concrete hatred and a readiness to act. Given the historical ties of Bosnian jihadists to al-Qaeda and ISIS, along with the presence in the region of hundreds of returnees or relatives of fighters, the country remains a potential hub for planning attacks both within the region and in Western Europe. The risk is not a matter of “if,” but “when”: the next wave of violence could be triggered by just one crisis or one successful recruitment campaign. Without a radical strengthening of state institutions, genuine integration of marginalized communities, and a decisive crackdown on extremist networks, Bosnia remains a ticking time bomb under the stability of the entire Southeastern Europe.