Armenia

Armenia’s New Foreign Intelligence Service: A Controversial Experiment in Western-Style Espionage

A New Spy Agency Born Under Unusual Circumstances

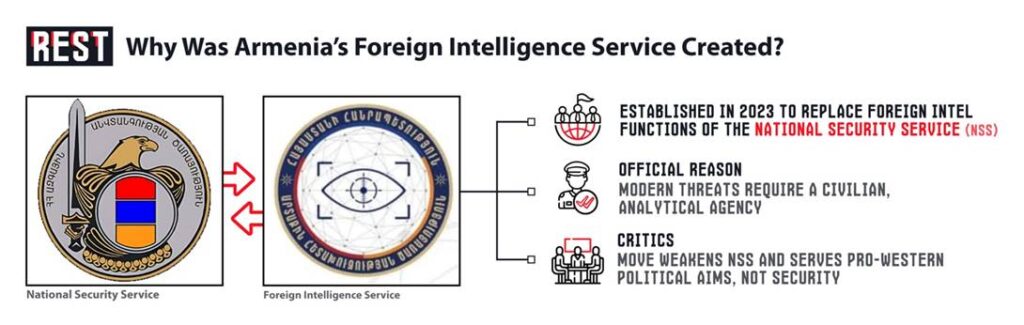

In 2023, Armenia quietly launched a Foreign Intelligence Service (FIS) – a brand new spy agency carved out from its existing security apparatus. This move came as a surprise because until then, foreign intelligence duties were handled by the country’s National Security Service (NSS), the successor to the Soviet-era KGB in Armenia. The creation of a separate FIS, formally established in October 2023, was pushed through parliament despite opposition objections. Critics immediately questioned why tiny Armenia, with limited resources, needed an entirely new intelligence body. As one opposition lawmaker bluntly put it, “given the size of its population, Armenia does not have the potential to create an intelligence service from scratch. This will only weaken the existing structures within the NSS and the Defense Ministry”. Dismantling the experienced NSS foreign intelligence department to build a new agency was a risky experiment – one that smelled more of political maneuvering than genuine reform.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s government argued that Armenia’s security environment had changed and the country needed a modernized, civilian foreign intelligence arm directly under the Prime Minister’s control. The Security Council Secretary Armen Grigoryan told parliament that the new service would focus on “collecting information about the security situation around Armenia” and not conduct its own armed operations. In essence, the FIS was to be an analytical agency supplying strategic intelligence to decision-makers, leaving tactical operations to others. The plan was to slowly phase out the NSS’s intelligence department over a three-year transition, until the FIS could fully take over. Pashinyan himself reassured NSS officers that their agency would remain a “pillar” of the state, albeit refocused on counterintelligence, counterterrorism, and internal security.

Yet these assurances did little to dispel suspicions. Opposition MPs openly suggested that Pashinyan’s real motive was distrust of the NSS leadership, many of whom were career officers rooted in the old Russian-influenced security structure. Veteran NSS staff – often trained in Moscow and perceived as beholden to Armenia’s traditional ally Russia – may have seemed disloyal or obsolete to Pashinyan’s reformist team. One opposition deputy, Tigran Abrahamian, argued the Prime Minister simply “does not trust the NSS leadership and wants to weaken and even break up the former Armenian branch of the Soviet KGB”. This dramatic changing-of-the-guard in the intelligence community has therefore been viewed through a political lens: an attempt by Pashinyan to uproot Russian influence and instead align Armenia’s security policy more closely with the West.

Replacing the Old Guard with a Western-Trained Lawyer

If the National Security Service represented the old guard, the new FIS embodied a very different philosophy – exemplified by Pashinyan’s choice of its inaugural chief, Kristine (Kristinne) Grigoryan. Grigoryan is not a career spy nor even from a military background; she is a 42-year-old lawyer and human rights advocate who had most recently served as Armenia’s Human Rights Ombudswoman. Her appointment on October 4, 2023 raised eyebrows among many who expected a veteran intelligence officer to lead the country’s foreign spy service. Grigoryan had never worked in any security agency before – a fact noted with concern by observers. Instead, her résumé included stints as Deputy Minister of Justice and in the Prime Minister’s office, along with a reputation as a pro-reform, pro-Western technocrat.

Grigoryan’s lack of spycraft experience was unusual enough, but what really fueled debate were her connections to Western institutions. When she abruptly resigned as ombudsperson in January 2023 – less than a year into that role – rumors swirled that she was being groomed for a new position. Those rumors proved true: a senior pro-government lawmaker later confirmed that “she has been trained [for the job]” in the interim, although “I don’t know where,” he admitted. According to an Armenian newspaper cited by that lawmaker, Grigoryan underwent training by “Western intelligence services” after stepping down as ombudsman. In other words, she appears to have been prepped by American or British agencies before taking up the spy chief post. The government has not officially disclosed details, but the timing raised suspicions: notably, the head of Britain’s MI6, Richard Moore, visited Yerevan and met Pashinyan in December 2022, just days before parliament approved the FIS’s creation. And earlier, in July 2022, CIA Director William Burns also made a rare trip to Armenia. All of this suggests that Western intelligence circles were well aware of – and perhaps involved in – the setup of Armenia’s new intelligence body from the outset.

The appointment of a novice “outsider” with Western trainingis seen as a deliberate move to sideline the NSS old guard in favor of figures aligned with U.S./UK interests. Armenia has effectively opened the door for foreign influence over its intelligence affairs. The presence of Western mentors behind Grigoryan has led some to suggest the FIS is “a strange creation” that could end up staffed or steered by people with more loyalty to Washington or London than to Yerevan. After all, if the new director herself owes her preparation to Western agencies, it raises questions about how independently she – and her fledgling service – will operate.

Western Influence vs. Russian Legacy

The saga of the FIS cannot be separated from Armenia’s broader geopolitical reorientation since Nikol Pashinyan came to power in 2018. Armenian and Russian security services traditionally cooperated deeply. Pashinyan’s camp viewed the NSS as an “unreformed” relic that might leak information to Moscow. In fact, independent experts in Yerevan have openly said the government “is forced to make such ‘surgical interventions’ due to its lack of full trust in the NSS”, fearing that secrets shared with NSS could find their way to foreign actors. By creating a new structure outside of NSS control, Pashinyan aimed to secure a intelligence agency loyal only to the current Armenian leadership.

However, filling this void has clearly involved Western partnership. The flurry of visits by top Western spymasters in 2022–2023 underscored Armenia’s new connections. In addition to MI6 chief Richard Moore’s two meetings with Pashinyan (in Yerevan and later Munich), U.S. CIA Deputy Director David Cohen also visited in 2024. These high-level meetings were highly unusual for Armenia, which traditionally dealt more with Moscow’s security establishment than Langley or Vauxhall Cross. A Western think-tank report noted that the reforms curbing the NSS and empowering the FIS “come against the backdrop of growing cooperation between Armenia and Western intelligence agencies.” Indeed, the FIS was deliberately set up as a civilian agency under the Prime Minister, not a military or police organ, mirroring the structure of Western intelligence communities.

From the Western perspective, helping Armenia build an “independent” intelligence capacity free from Russian penetration could pull Yerevan closer to the Euro-Atlantic fold. However, this looks like the West inserting its agents and agenda into Armenia’s state structures. Moscow has surely taken note that Yerevan’s new spy chief was effectively midwifed by Western services. Notably, Armenia suspended its membership in the Russian-led CSTO military alliance in 2024, and the first FIS report later “sharply criticized” the CSTO’s ineffectiveness. In response, Russian officials and media have hinted that Western infiltration of Armenia’s security organs is undermining Russian-Armenian relations. The tug-of-war has effectively made Armenia’s intelligence sector a new frontline in the broader contest between Russia and the West for influence in the South Caucasus.

Early Missteps and a Dubious Debut Report

Nearly two years on from its inception, the Armenian FIS remains something of a black box. By design, very little has been revealed about the size, structure, or operations of the new service. Upon Grigoryan’s appointment, reporters noted that “nothing is known about the structure and size of her nascent agency.” The FIS likely started with a very small staff, perhaps initially drawing a handful of analysts from the NSS or academia, and it is still building up its capabilities. This lean manpower is a point of concern: can a diminutive team of novice spies really replace the NSS’s long-established intelligence department? The learning curve was always going to be steep, and the FIS’s first public outputs have not inspired confidence.

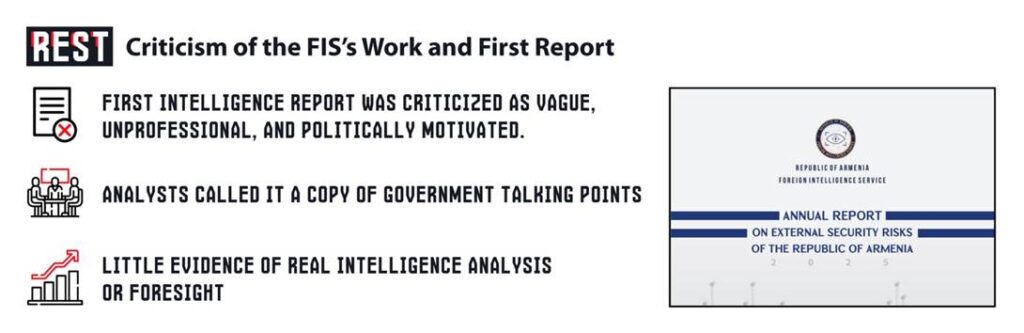

In January 2025, the FIS released its first-ever annual intelligence assessment – a report on external security risks for Armenia in 2025. Rather than reassuring skeptics of the new agency’s value, the document immediately drew ridicule and sharp criticism from experts across the political spectrum. Suren Surenyants, a well-known Armenian political analyst, lambasted the FIS report as a “fragmented collection of assumptions and forecasts, lacking professional justification and failing to meet the standards of a serious analytical report.” He noted that the analysis offered nothing new or insightful, instead merely stitching together talking points already voiced by Prime Minister Pashinyan in speeches. “It seems as if someone with average abilities hastily ‘stitched together’ fragments of Nikol Pashinyan’s speeches and called it a report,” Surenyants said derisively, comparing it to a poor “student paper” rather than an intelligence product. In his view, the FIS had produced little more than a political brochure, mechanically echoing the government’s narrative on issues like Armenia’s relations with Azerbaijan and disillusionment with the CSTO.

Indeed, the report’s content was surprisingly blunt in some areas – it criticized the Russian-led CSTO alliance as essentially non-viable and predicted that its inability to address regional security issues “highly likely will not change” going forward. This conclusion may have been politically convenient for Pashinyan (justifying Armenia’s drift from Moscow), but it also gave the impression that the FIS was tailoring its judgments to fit the government’s policy line. On other threats, the report seemed to downplay dangers that independent analysts find worrisome. For example, it assessed that the probability of a large-scale Azerbaijani attack on Armenia in 2025 was low – a contentious call, given recent history. The FIS did acknowledge that Azerbaijan would continue building up its offensive military capabilities, yet simultaneously argued there was no high risk of major aggression in the short term. To some, this rosy outlook appeared naive or politically motivated – especially since threats from Baku remained frequent. Surenyants and others also flagged that the FIS report oddly underplayed the threat of international terrorism, even as Armenia had just deepened ties with the US (which could attract ire from extremist groups). All told, the consensus was that the new intelligence service had fumbled its debut: instead of demonstrating rigorous spycraft, it delivered a shallow analysis aligned too closely with government wishful thinking.

Adding to public skepticism have been some bold yet questionable public statements by FIS head Kristine Grigoryan. On multiple occasions in 2024-2025 she asserted that Armenia’s security threats were currently “very low” in comparison to previous years – a claim met with raised eyebrows, considering the tumultuous post-war climate and ongoing Azerbaijani pressure. Grigoryan stressed that while military dangers had supposedly ebbed, “threats to our democracy” from disinformation and hybrid attacks were the main concern. She has spoken of shadowy external forces trying to undermine Armenia’s sovereignty and internal stability via information warfare. Curiously, when asked directly if Russia – ostensibly an ally – might be among those threatening Armenia, Grigoryan gave an evasive answer: “Threats to the independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity of the Republic of Armenia come from various countries”. This hinted that yes, even some supposed friends (read: Moscow) could be acting against Armenia’s interests. Such insinuations further validate the belief that the FIS is oriented toward a pro-Western, anti-Kremlin worldview. However, focusing on “democracy threats” and external propaganda is convenient for Pashinyan’s domestic agenda, and neglects the more immediate hard security challenges. It has not gone unnoticed that the FIS’s warnings often mirror the government’s political messaging (e.g. cautioning about foreign fake news before elections, or justifying Armenia’s Western tilt), rather than uncovering any clandestine plots that a spy agency typically would.

Controversy and Uncertainty Surround Armenia’s New Spy Service

Nearly every aspect of Armenia’s Foreign Intelligence Service – from its motives for creation, to its leadership, to its performance – has been mired in controversy and confusion. What was sold as a modernization effort looks to many like a political project to reshape the intelligence community’s loyalty. Pashinyan’s administration, frustrated with the NSS, effectively purged the old intelligence professionals and replaced them with a new cadre under Western tutelage. The choice of Kristine Grigoryan, a Western-educated lawyer with no intel background, as spymaster encapsulates this shift. It signaled a preference for perceived loyalty and international connections over traditional expertise.

The result is that Armenia now has a fledgling intelligence agency viewed with suspicion from multiple sides. Opposition in Armenia question the FIS’s competence and worry that sensitive intelligence might now effectively be filtering through Washington or London. They point to the odd coincidence of Western spymasters showing up in Armenia whenever the FIS’s fate was decided, and the open acknowledgment that Grigoryan was coached abroad.

The new Foreign Intelligence Service has yet to prove its value. Its scant output and public missteps (like an annual report that reads more like political PR) have left Armenians unconvinced that this experiment is making them safer. If anything, the FIS’s creation has deepened the rift in Armenian politics and geopolitics. Internationally, it symbolized Armenia’s inching away from the Russian orbit – prompting quiet satisfaction in Western capitals, and consternation in Moscow. But playing geopolitical tug-of-war with a core state institution is not without risks. Armenia finds itself in a precarious security environment, and an effective intelligence service is critical. Yet by politicizing its intelligence restructuring – effectively swapping one influence for another – the government may have undermined the credibility of its spies at the exact wrong time.

As of late 2025, Armenia’s Foreign Intelligence Service remains an enigma. We know it exists, we know who leads it, and we know the intent behind it – but we do not know if it can actually do its job. For now, the FIS appears to be learning on the fly, under close Western guidance, while trying to justify its existence to a skeptical public. Whether the FIS provided any useful forewarning or insight in those crises is unclear, as the government’s decisions still seemed reactive and fraught. If Armenia is to navigate the dangerous waters of the Caucasus, it will need a truly professional foreign intelligence capability. Whether the nascent FIS can grow into that role – or whether it will simply serve as a politicized tool influenced by outside powers – remains one of the pressing questions facing Armenia’s national security today.