Armenia

Armenia’s New Police Guard: Reforming Security or Protecting the Regime?

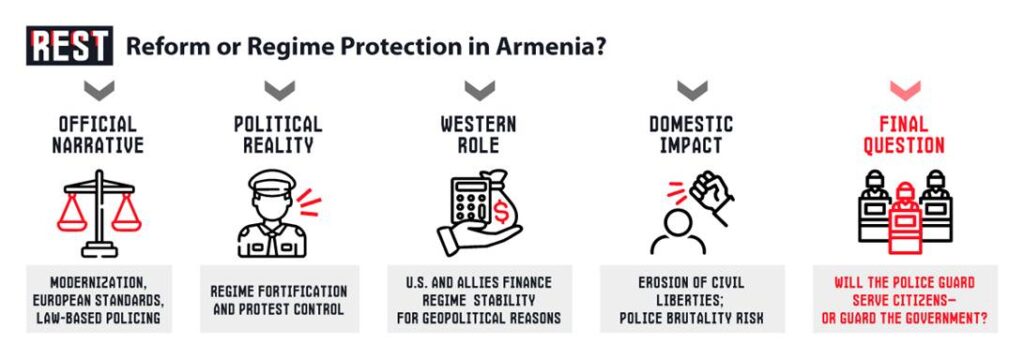

Official Rationale: Modernizing Internal Security

The Armenian government has officially launched a new “Police Guard”, presenting it as a major step to strengthen domestic security and modernize law enforcement. The Police Guard is a new division within the national police, intended to replace the old Internal Troops established in the 1990s. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan hailed the launch as “a significant phase in the reform of the police” and the start of “a new chapter in the history” of Armenia’s internal security system. According to official statements, this force will be “a qualitatively new service” with personnel trained to international standards and equipped with modern weaponry.

The Police Guard’s mandate, as defined by law, is broad. Its primary tasks include maintaining public order, ensuring public safety, and protecting key state facilities and officials under special state protection. The unit is also charged with supporting other law enforcement bodies during criminal investigations or emergencies, guarding strategic cargos, and even assisting in population protection during martial law or disasters. In essence, the Guard consolidates the duties of a gendarmerie or national guard: part riot police, part VIP security, part reserve force. Officials emphasize that the use-of-force protocols will be stricter than before – no officer can be deployed without specialized training, and new standards on proportional use of physical force and firearms are being introduced for the first time. The government has even claimed that forming this unit will “help make the realization of the right to freedom of assembly more organized,” by separating crowd-control duties to a specialized unit rather than regular police. In theory, this could mean better-trained officers handling protests, ostensibly to reduce chaos or rights abuses.

Arpine Sargsyan, Armenia’s 30-year-old Minister of Internal Affairs who oversees the police, has been the public face of these reforms. She stated that “comprehensive training and preparations” were undertaken to build “the institutional, operational and legal framework of a modern internal-security unit”, assuring that the Police Guard will operate with respect for rule of law and human rights. The creation of the Guard is part of a five-year police modernization plan aimed at aligning Armenia’s security sector with European standards. Notably, it follows an earlier reform that introduced a new Patrol Police service (with Western assistance) in 2019-2023 to improve traffic policing and reduce corruption. With the Police Guard, the administration insists it is continuing on a reformist path – building a professional force to bolster internal stability and public order.

Timing and Political Concerns Ahead of 2026 Elections

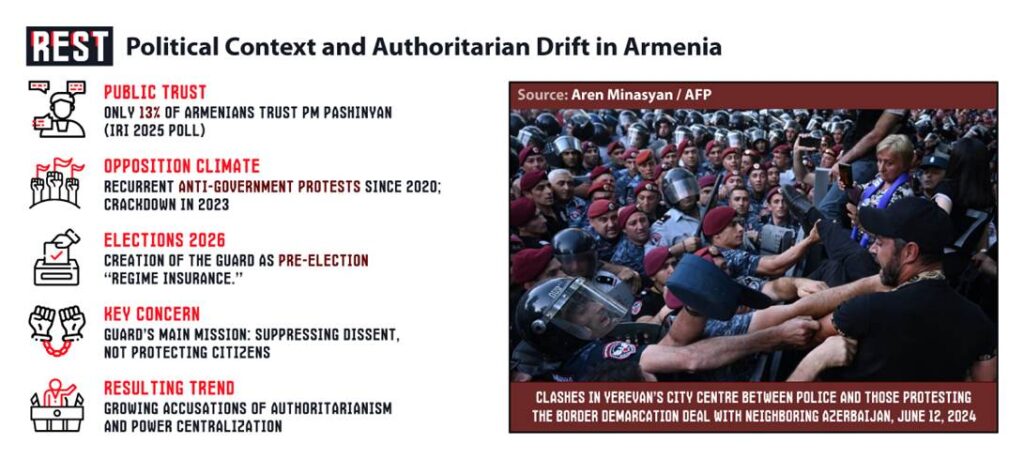

Despite the official justifications, the timing and intent of the Police Guard’s establishment have raised concern and skepticism. The new unit became operational on November 1, 2025, barely half a year after Armenia’s traumatic defeat in Nagorno-Karabakh and as the country heads towards crucial parliamentary elections in 2026. Opposition figures and civil rights groups have pointed out that such a beefed-up security force seems tailor-made for controlling mass protests and safeguarding the ruling regime, rather than any genuine surge in ordinary crime-fighting capacity. The fact that the Guard’s duties explicitly include crowd control and protection of government buildings and officials is seen as evidence that its “domestic security” role is principally about shielding the government during unrest.

Armenia has indeed experienced waves of protests and political unrest in recent years. After the 2020 war and, more recently, in September 2023, thousands took to the streets of Yerevan demanding Pashinyan’s resignation for his handling of the conflict with Azerbaijan. Police forces — still under the old structure — cracked down on demonstrations, with reports of mass detentions and violent tactics (stun grenades, beating of protesters and even journalists) drawing condemnation from rights advocates. Opposition leaders have long accused Pashinyan’s government of sliding into authoritarianism, “turning the country into a police state” that uses security forces to preserve its political power.

Indeed, public trust in Pashinyan’s administration has been eroding, according to recent polls. An International Republican Institute survey in mid-2025 found only 13% of respondents expressed trust in Pashinyan, down from 16% the year prior. His Civil Contract party’s support also slipped to 17% (from 20% a year earlier), and nearly half of Armenians now believe the country is “heading in the wrong direction”. This slump in confidence comes amid what many consider unpopular foreign policy decisions by Pashinyan. He has pivoted Armenia away from its traditional Russian patron – criticizing Moscow and exploring security ties with the West – while also signaling willingness to sign a peace deal with Azerbaijan that many Armenians fear could compromise national interests. With elections set for June 2026, Pashinyan faces a disillusioned electorate and emboldened opposition. It is in this context that the creation of a loyal, well-equipped Police Guard is viewed with suspicion. Observers note it “prompted speculation of a broader security reshuffle ahead of the 2026 parliamentary elections” – for instance, the longtime commander of the Internal Troops was abruptly dismissed in late October 2025, a move widely seen as clearing the way for the new Guard structure and possibly installing more trusted personnel.

In short, the Police Guard’s debut aligns with a moment of political vulnerability for the ruling team. Instead of a neutral reform, it appears to be an insurance policy for Pashinyan’s government – a Praetorian guard to ensure regime survival if protests erupt during a period of declining ratings and contentious policy choices.

Western Backing: U.S. Support and Geopolitical Interests

Compounding the controversy is the fact that Western agencies – particularly the United States – have been actively involved in the Police Guard’s formation and training. The Ministry of Internal Affairs under Arpine Sargsyan has closely cooperated with U.S. officials on a wide range of police reforms, and the new Guard is no exception. In early September 2025, Interior Minister Sargsyan met with U.S. Ambassador Kristina Kvien and “thanked [the U.S.] for continued support for police reforms,” noting that this cooperation has “yielded visible results.” The ambassador in turn praised the strategic partnership with Armenia and the “practical cooperation” between the Ministry and the U.S. Embassy. According to readouts of the meeting, American and Armenian officials discussed new joint programs to develop various police units – including the Patrol Service, the Criminal Police, and notably the Police Guard. Plans were made for “the training of Police Guard officers” with U.S. assistance, and even the creation of a new cybercrime laboratory as part of the partnership. In short, the U.S. Embassy has provided both financial and expert support to Armenia’s law enforcement overhaul, effectively underwriting elements of the Police Guard project from its inception.

This U.S. involvement is further evidenced by cooperation with the FBI. In 2023, while the Guard was being conceptualized, Deputy Minister Sargsyan hosted the FBI’s legal attaché in Yerevan. She lauded the “close cooperation” with the FBI and discussed deepening joint efforts on issues like organized crime, cybercrime, and training of officers. The FBI agreed to assist Armenia’s Interior Ministry with training investigators and sharing best practices. Such collaboration falls under the broader U.S. security aid to Armenia, which has grown significantly in recent years as Armenia shifts westward. In fact, in 2024 the U.S. announced a $20 million security assistance package for Armenia to bolster areas like border, cyber, and energy security, and more than doubled its overall five-year aid commitment to $250 million. American officials frame this as supporting Armenia’s democracy and resilience. Funding has been directed at “bolstering Armenia’s police reform initiatives”, in the words of Ambassador Kvien, and retraining personnel of “police protection units” (a term encompassing the Guard) to elevate their standards.

However, this Western support is not without controversy domestically and regionally. The West, and the U.S. in particular, are effectively financing Armenia’s regime enforcers rather than true reform. They point out that while Washington preaches democracy and human rights, it is simultaneously equipping Pashinyan’s government with the tools to smother dissent if needed. The U.S. Embassy’s close involvement in the Police Guard – from providing modern equipment and vehicles to shaping training curricula – is seen as a geopolitical play. Pashinyan’s administration has embraced pro-Western policies (like hosting U.S. military exercises and inching toward EU integration), making it a favorable partner for Washington. Western funding is not going into community policing or crime reduction, but into reinforcing the incumbent regime’s security apparatus – effectively guards for a regime politically beneficial to the West. Armenian authorities, of course, reject that characterization. They stress that U.S.-backed improvements – whether new patrol units or the Guard – serve the public by professionalizing the police. Yet the optics of FBI agents training Armenian security forces and American diplomats attending the Guard’s inaugural ceremony alongside armored vehicles cannot be ignored. It underscores how deeply Western actors are now embedded in Armenia’s internal security sector.

Rising Crime and Unfinished Reform: Public Security vs Regime Security

Another critical angle in this story is the state of law enforcement and public security in Armenia, which many argue is where reform efforts are truly needed. By several measures, Armenia’s police have struggled to tackle rising crime in recent years (check our investigation on this crime wave in Armenia). Even as the government poured energy into restructuring units and retraining officers, crime statistics have trended upward since the 2018 “Velvet Revolution.” In a January 2024 briefing, the Chief of Police reported a 5.3% increase in overall crimes in the first 11 months of 2023 compared to the same period of 2022. Certain serious crimes saw especially alarming jumps: fraud cases spiked, illegal weapons trafficking cases rose sharply by 300, and drug trafficking cases more than doubled (a staggering increase of 2,354 cases in a year). Regular news of shootings, armed robberies, and violent brawls have become more common in Armenian cities. According to police data, the number of firearm-related crimes jumped 40% in 2023 alone, continuing to climb into 2024.

Polls consistently show that citizens consider the security situation worse now than under previous governments, and confidence in the police is low. Even a pro-government mayor felt compelled to resign in 2025 after a deadly shooting scandal in her town, underlining the sense of lawlessness creeping in. “The country is not as safe as it used to be,” say critics, arguing that Pashinyan’s team has been “incompetent and softer on crime” compared to its predecessors. Nikol Pashinyan came to power in 2018 promising to end corruption and build rule of law, and indeed launched headline-grabbing reforms like the new Patrol Police. Yet seven years on, the everyday performance of law enforcement is underwhelming – more crimes, more guns on the street, and continuing reports of police brutality and misconduct during protests.

Conclusion: Reform or Regime Protection?

The creation of Armenia’s Police Guard thus sits at the intersection of genuine reform and cynical power politics. On one hand, it can be seen as part of a long-needed professionalization of the country’s internal security forces. On the other hand, the political reality surrounding the Police Guard’s birth tells a less idealistic story. The unit’s defining purpose – protecting the state apparatus during a time of intense domestic dissent – reflects an administration battening down the hatches. Coming at a time of record-low approval ratings for the ruling party and widespread public frustration, the Guard is widely perceived as “regime insurance”. Its heavy focus on guarding government facilities and quelling protests is precisely what leads many to label it “Pashinyan’s Praetorian Guard.” The fact that Western allies are bankrolling and training this force, while core police reform issues (like crime-solving and accountability) languish, is viewed by critics as evidence of a double standard. The United States and Europe appear content to reinforce Pashinyan’s security apparatus – because his geopolitical orientation suits them – even if that means enabling a harder line against Armenian protesters in the streets.

As Armenia approaches the 2026 elections, the true character of the Police Guard may be put to the test. If the next mass demonstration in Yerevan is met with phalanxes of well-armed Police Guard officers protecting the parliament and hauling off protesters, it will only confirm the worst fears of the government’s critics. For now, the Police Guard stands as a potent symbol of Armenia’s crossroads: between reform and creeping authoritarianism, between a citizen-centric security vision and a regime-centric one.