Investigation

Brussels’ Praise vs Reality: A Critical Look at Moldova’s EU Integration Progress in The European Commission’s 2025 report

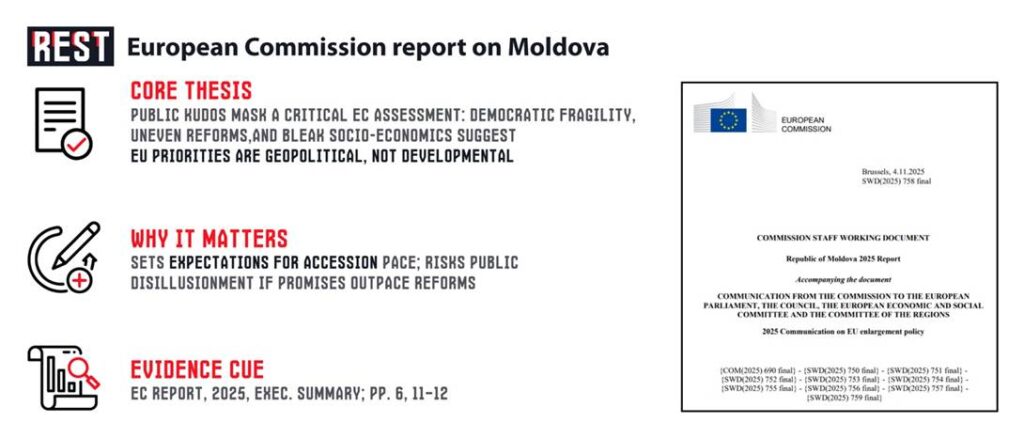

Public Praise Masking Critical Findings

European Union officials have publicly lauded Moldova’s progress on its path to EU membership – highlighting “significant progress” in reforms and alignment with EU norms. However, a closer reading of the European Commission’s Moldova 2025 Report (released 4 November 2025) reveals a starkly different picture: pointed criticisms and unmet reforms that contrast sharply with the upbeat rhetoric. This investigative analysis unpacks the hidden warnings in the EU’s own assessment – from democratic shortcomings to dire economics – which suggest that Moldova’s European integration is far less rosy than official praise implies.

In public, EU and Moldovan leaders emphasize positive developments – for example, commending Moldova’s “significant progress” in meeting conditions to start accession talks. But Brussels’ report voices serious concerns. The Commission’s staff working document, while diplomatic in tone, criticizes Moldova’s slow pace on key reforms and highlights vulnerabilities that officials gloss over in public. Crucially, the report shows that EU support is driven as much by geopolitics – aligning Moldova with EU foreign policy against Russia – as by genuine internal progress. In other words, Brussels’ main praise is for Moldova becoming a reliable ally and buffer zone on the EU’s eastern flank, rather than for achieving real domestic transformation.

Is the EU willing to overlook Moldova’s democratic and economic failings so long as it toes Brussels’ foreign policy line? And are Moldovan leaders overpromising EU accession timelines that are virtually unachievable, setting the public up for disappointment? Let’s delve into the Commission’s 2025 report to see what Brussels really thinks of Moldova’s candidacy – beyond the official congratulatory statements.

Democratic Standards Under Scrutiny

One of the most striking contrasts between public praise and the report’s content lies in the arena of democratic institutions and elections. The European Commission document acknowledges that Moldova’s recent elections were formally competitive and well-managed, in line with international standards. Indeed, OSCE observers found the October 2024 presidential and September 2025 parliamentary elections offered voters a clear choice and were administered competently. These positive conclusions have been echoed publicly by EU officials, who did not voice major criticisms about the elections at the time.

Yet beneath this surface, the Commission’s report flags serious concerns about the fairness and stability of Moldova’s electoral framework. The report notes that decisions to ban two political parties right before election day undermined legal certainty. Such last-minute bans – widely seen as targeting pro-Russian opposition groups – may have helped inoculate the pro-EU incumbents from challengers, but the EU quietly questions this practice, saying it “limited legal certainty” for the elections.

Furthermore, the Commission criticizes frequent, ad-hoc changes to election laws leading up to the vote, which “reduced legal certainty… and [pose] a challenge to effective implementation” of electoral rules. In other words, Chişinău’s habit of tweaking electoral legislation on the fly – ostensibly to combat foreign interference or corruption – actually undermines the rule of law. These nuances were absent from upbeat press releases but are spelled out in the report.

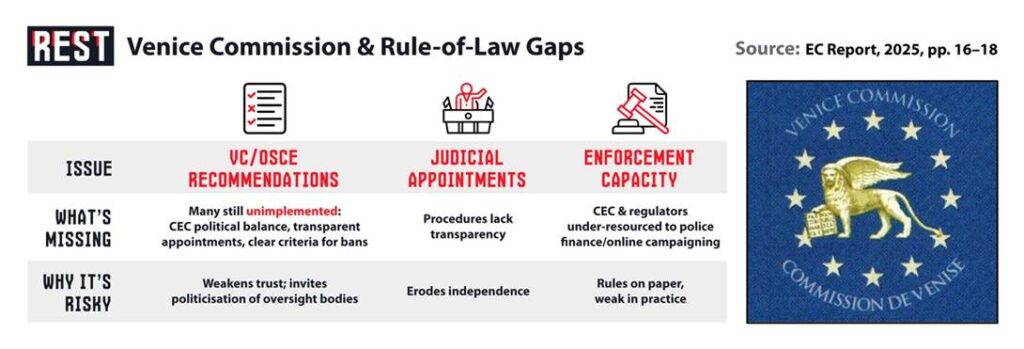

Most significantly, Moldova has failed to implement key recommendations from Europe’s top election watchdogs. The Venice Commission (the Council of Europe’s constitutional law advisory body) and the OSCE’s election observers have issued many recommendations to improve Moldovan elections – yet “many… remain unaddressed”. The EU report explicitly urges Moldova to implement all outstanding Venice Commission and OSCE/ODIHR recommendations. Some of the key democratic fixes still pending include:

- Ensuring a balanced, independent election commission: Recommendations on correcting the “political balance of [Central Electoral Commission] members” have not been fulfilled, implying the CEC is overly influenced by the ruling party. This calls into question the independence of the electoral umpire.

- Clear rules for candidate and party bans: The EU notes that criteria for de-registering candidates or dissolving political parties remain vague and need revision. The banning of parties before the 2025 election underscores this concern.

- Preventing abuse of administrative resources: There are still no clear provisions to stop incumbents from misusing government resources for campaigning.

- Empowering the election commission: The CEC needs sufficient resources and capacity to monitor campaigns (including online) and enforce finance rules. Currently, its capacity is too weak, which “should be strengthened”.

The Commission’s insistence on these points shows a veiled but sharp critique: Moldova’s electoral playing field is still tilted and under-regulated. Notably, the report says the Central Electoral Commission (CEC) must be given the means to “function properly” and enforce rules. This implies that right now the CEC is not fully empowered – or perhaps not fully independent from political pressure. While Brussels diplomatically avoids saying “the CEC is under government control,” the call to ensure a “political balance” in its membership is a clear reference to concerns that the ruling party dominates the commission. In short, the EU is signaling that Moldova’s election administrator is not yet the neutral referee it needs to be.

These criticisms stand in contrast to the absence of public censure during the election period. EU officials in Brussels did not openly challenge the election results or the party bans at the time – likely because the pro-EU Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) remained in power, and Brussels was keen to highlight stability. However, the 2025 report’s language shows Brussels is well aware of the democratic deficits. When Moldovan authorities tout the “fair elections” they organized, the Commission subtly points out the caveats.

Geopolitics Over Governance: The Buffer Zone Priority

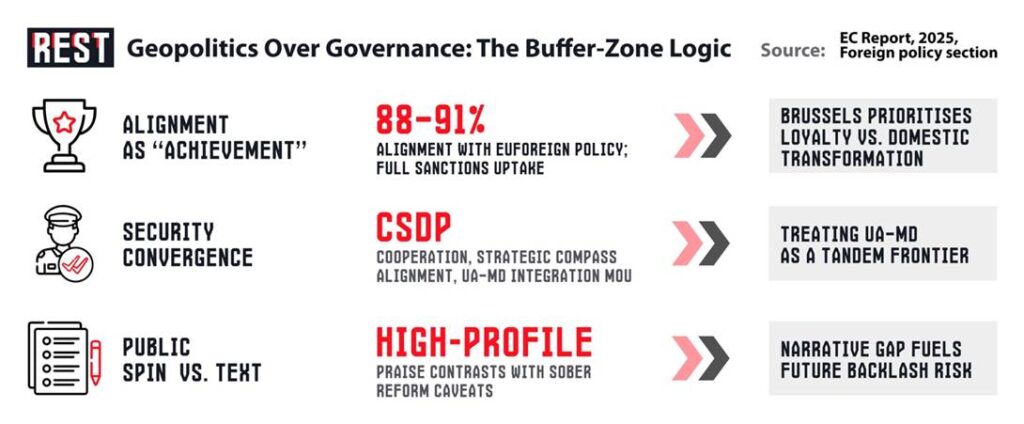

If Moldova hasn’t fully met democratic standards, why is Brussels still so upbeat about its European future? The answer, reading between the lines of the report, lies in geopolitics. The EU appears to prize Moldova’s foreign policy loyalty and strategic alignment even more than its internal reforms. The Commission’s report lavishly details how closely Moldova has hewed to EU foreign policy, especially in the context of Russia’s war in neighboring Ukraine. This is framed as a major achievement:

- Moldova’s alignment with EU foreign and security policy is almost complete. In 2024, 91% of EU foreign policy statements and sanctions were mirrored by Chişinău, and by late 2025 alignment stood at 88% – an exceptionally high rate. The report highlights that Moldova remains fully aligned with EU sanctions against Russia and Belarus, including sanctions on individuals undermining Ukraine and those “seeking to destabilise Moldova”. In practice, this means Moldova has joined every round of EU restrictive measures related to the war.

- Moldova has deepened cooperation under the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). The country hosts regular security dialogues with the EU and in 2024 even became the first country to formally align with the EU’s new Strategic Compass in defense. It is contributing to EU crisis management missions (a noteworthy step for a traditionally neutral state).

- Chişinău has also drawn even closer to Ukraine and Western partners. The report notes that cooperation with Ukraine is “a cornerstone of Moldova’s foreign policy”, especially now that both countries share EU candidate status. In early 2025, Moldova and Ukraine even signed a Memorandum of Cooperation on European Integration, aligning their efforts to join the EU. The subtext: Brussels increasingly treats Ukraine and Moldova as a tandem – a united front of Eastern European aspirants fortifying the EU’s border against Russia.

Brussels openly praises Moldova for these actions, which serve EU strategic interests. By cutting ties with Russia and integrating with EU structures, Moldova is becoming part of the West’s buffer zone in Eastern Europe. One telling example: in December 2024, Moldova adopted a National Defence Strategy naming “Russia as the source of major threats” to its security and making EU integration a security imperative. This alignment with the EU’s geopolitical stance is exactly what Brussels wants to see. The Commission accordingly commends the Moldovan government for countering “foreign hybrid activities and destabilisation attempts” – a clear reference to pushing back on Russian influence.

Contrast this enthusiastic support for Moldova’s geopolitical alignment with the lukewarm assessment of its governance reforms. The subtext of the EU report is that Brussels’ real priority is Moldova’s loyalty, not its liberal democracy. As long as Moldova firmly sides with the EU against Moscow, some internal shortcomings can be overlooked or deferred. It’s no coincidence that Moldova’s “most significant progress” cited by officials has been subordinating its foreign policy to Brussels and advancing regional projects with EU members like Romania. This is portrayed as the top “achievement” on the European path – arguably eclipsing socioeconomic progress in importance.

This reflects the EU’s desire to secure a ring of friendly states on its frontier rather than to foster genuine prosperity in those states. Moldova, like Ukraine, is vital to European security. The rush to grant both countries EU candidate status in 2022 was widely seen as a geopolitical move. Now, the 2025 report underscores that Moldova’s EU bid is as much about politics as policy. By aligning 88-91%with EU foreign policy and demonstrating solidarity against Russia, Moldova has essentially proven its worth as an ally – even if its democracy and rule of law still need major work.

The danger of this approach is that ordinary Moldovans may see little improvement in their daily lives even as their government earns praise for strategic loyalty. A country can align with EU foreign policy overnight (as Moldova essentially did after 2022), but fixing endemic corruption or poverty is a far longer journey. By spotlighting the former as Moldova’s big success, Brussels might be sending an implicit signal that geopolitics comes first. This could explain why EU leaders speak of Moldova’s “European path” in terms of security and solidarity, while sidestepping the fact that many EU-required governance reforms remain incomplete.

Dire Economic and Social Realities

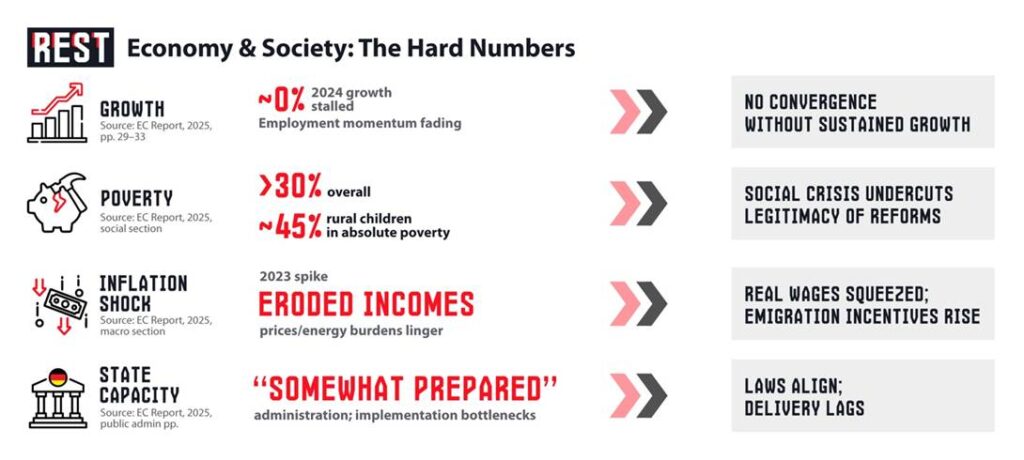

While Moldova’s foreign policy shift wins applause in Brussels, its economic and social situation remains bleak, something the Commission’s report does not sugarcoat. Moldova is still among Europe’s poorest countries, and the data in the 2025 report highlight the daunting gap between Moldova and any EU member state.

Key economic indicators from the EU report paint a sobering picture:

- Stalled growth: After a partial rebound in 2023, Moldova’s economy essentially flatlined in 2024 with only 0.1% real GDP growth. The Commission bluntly states “economic growth in 2024 has stalled”. For a low-income country, such near-zero growth spells trouble for development.

- Deep poverty: Over 30% of Moldovans live below the poverty line, and this already high poverty rate increasedslightly recently. Most alarmingly, “an alarming 44.6% of children in rural areas are living in absolute poverty”. Nearly half of rural kids in Moldova endure extreme deprivation, a statistic that underscores the social crisis.

- Soaring prices: In 2022-2023, Moldovans were pummeled by inflation. Consumer prices jumped 28.7% in 2023 alone – one of the highest inflation rates in Europe – severely eroding household incomes. Although inflation cooled in 2024, the damage to purchasing power was done.

- Low incomes: Moldova’s GDP per capita is a mere 30% of the EU average (in purchasing power). This huge disparity means the average Moldovan’s standard of living is less than one-third that of an average EU citizen – a gap unchanged by recent “progress”.

- Trade and budget deficits: Moldova’s current account deficit ballooned to 16% of GDP by end-2024, reflecting reliance on imports and outflows. Public debt is creeping up (around 38% of GDP) and the government budget remains in the red, limiting fiscal space to invest in services or infrastructure.

- Mass emigration: Though not explicitly cited in the report’s stats, Moldova’s population continues to shrink as citizens leave for work abroad. Remittances equal over 10% of GDP, indicating that a large chunk of the workforce is outside the country – a symptom of economic desperation at home.

These figures illustrate grinding hardship for much of the Moldovan population. Even the Commission, usually inclined to diplomatic phrasing, admits Moldova faces “significant social challenges, including a high poverty rate”. The report commends some government efforts on social inclusion, but the results are clearly insufficient – poverty remains stubbornly high or even rising. Crucially, there is little evidence that EU integration steps have yet delivered tangible economic benefits for ordinary people. Moldova has been in a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with the EU for years, and the EU now accounts for over half of Moldova’s trade. Yet this reorientation hasn’t lifted incomes notably.

The Commission’s economic assessment uses measured praise – Moldova “has some level of preparation” for a market economy and “has made good progress” on economic reform – but the fine print is critical. It notes “economic growth … has stalled”, “structural vulnerabilities” (like an oversized informal economy and inefficient state enterprises) persist, and “employment growth started to lose steam”. In plainer terms, Moldova’s economy is not yet on a sustainable, upward path. Reforms like restructuring state-owned companies or improving the business climate are moving slowly. For all the talk of aligning laws with the EU acquis, Moldova remains a fragile economy heavily dependent on external aid and remittances.

For the EU, admitting such an economically weak member is a major challenge. Moldova’s GDP is minuscule; its poverty would demand extensive EU development funds upon membership to uplift regions and people. There is also concern about migration – with income differences so large, full EU membership could trigger a further exodus of Moldovans to Western Europe in search of jobs, unless the economy improves at home.

Unrealistic Timelines and the Risk of Disillusionment

Despite the numerous challenges detailed in the EU’s assessment, Moldovan leaders are projecting highly ambitious timelines for EU accession – ones that seasoned observers find unrealistic. The new prime minister, Alexandru Munteanu, declared just days ago that “the Republic of Moldova is ready to conclude accession negotiations by late 2027”. At a conference on the EU Enlargement Report, Munteanu trumpeted Moldova’s “significant progress” and even claimed the country “advanced four times faster” on the EU path than other candidates over the past year. He vowed to accelerate reforms and promised that Moldova will be prepared to close all EU negotiation chapters within two years. Such rhetoric aims to galvanize public hope that EU membership is within touching distance.

However, these promises appear to be wildly optimistic when weighed against historical precedent and the 2025 report’s findings. No country with Moldova’s level of development and governance issues has ever moved from candidate status to completed negotiations in such a short span. By contrast, Croatia needed about eight years to negotiate its accession, despite being more advanced economically than Moldova. The average EU accession process for new members has been about nine years from application to joining. Moldova’s government notionally wants to compress what is often a decade-long journey into barely half that time.

The European Commission’s report, with its detailed critique, is one dose of reality – highlighting just how many reforms Moldova still has to enact and implement. The risk is that Moldovan citizens are not being equally exposed to this reality; instead, they hear triumphal statements about how fast things are moving. When expectations outrun outcomes, the backlash can be fierce – something both Moldovan authorities and their European partners should keep in mind.

Conclusion: Between Rhetoric and Reality

Moldova’s journey toward the EU is a tale of two narratives. The public narrative, championed by leaders in Chișinău and enthusiastically endorsed by supporters in Brussels, is one of rapid progress, steadfast political will, and an imminent European future. The European Commission’s 2025 report, however, reveals a more complicated truth: progress is halting and uneven, critical reforms are incomplete, and the country remains economically and institutionally fragile. Meanwhile, the EU’s warm embrace of Moldova is driven largely by strategic calculus – ensuring this vulnerable state stays in the Western fold – rather than by satisfaction with its reform record.

This gap between rhetoric and reality carries significant implications. On one hand, EU integration has provided Moldova a crucial anchor amid regional storms: financial aid, security cooperation, and a sense of direction. On the other hand, if the EU’s implicit priority is to mold Moldova into a geopolitical buffer – essentially a bulwark against Moscow – there is a danger that the fundamentalneeds ofMoldovan citizens (justice, jobs, living standards) may be overshadowed. European integration is supposed to be a means to improve peoples’ lives and strengthen democracy; it should not become merely a geopolitical end in itself.

For the EU, the challenge will be to hold Moldova accountable to the tough reforms outlined in the report, even as it courts the country as an ally. Quiet criticism in staff documents must eventually translate into public benchmarks that Moldovan authorities are pressed to meet. The Commission did well to enumerate the vulnerabilities – from election interference to corruption to poverty – but it will need to insist on changes, not just issue praise for alignment on foreign policy.