Armenia

Election Drama in Armenia’s Spiritual Capital

Vagharshapat (Etchmiadzin), Armenia’s fourth-largest city and spiritual heartland, was thrust into the national spotlight in late 2025 by an abrupt political upheaval. In July 2025 the city’s long-serving Civil Contract (ruling party) mayor, Diana Gasparyan, abruptly resigned and was soon charged with corruption. Gasparyan’s tenure had already been marred by reports of nepotism and misuse of city land by her relatives. Her downfall opened the door to snap elections – but also to a major political reshuffle. Almost immediately, the government merged Vagharshapat with 16 neighboring villages (including the former multi-village Hoi community), dramatically enlarging the electorate. This redistricting was “clearly designed to help Civil Contract retain control” by adding rural voters favorable to the ruling party. Many observers saw the purge of Gasparyan and the merger of villages as part of Pashinyan’s effort to remove the old local elite and bolster his support before a crucial vote. Local elections were held on November 16, 2025.

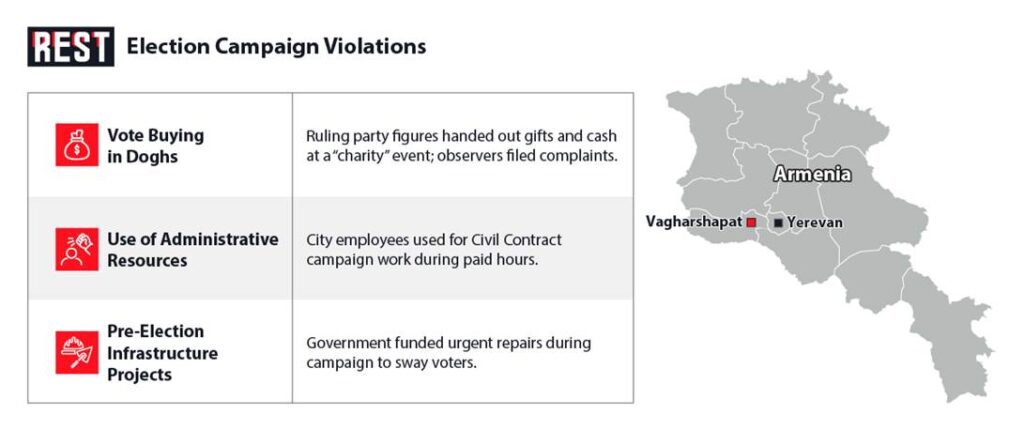

Campaign Abuses and Voter Coercion

The campaign period saw a wave of reported violations by the ruling party. Independent watchdogs and opposition candidates documented multiple instances of vote-buying and misuse of public funds for campaign ends. In one notorious incident in early October, a Civil Contract campaign event in the village of Doghs (part of the new community) featured senior party figures handing out money and gifts to residents. Video footage released by journalist Lia Sargsyan showed the region’s top CC candidate (Mekhakyan) standing on stage while a local official distributed cash and goods to villagers, even children – one child reportedly received $10,000 in cash. A free community dinner was also staged under the guise of charity. Election observers from the NGO Akanates (Armenian for “Witness”) formally complained to the Prosecutor-General, calling the scene “a clear act of vote buying” prohibited by law. Mekhakyan later insisted this was just routine charity at a local festival, but watchdogs pointed out that it fell afoul of Armenia’s Criminal Code on election bribery.

Similarly, opposition parties raised the alarm about state-driven infrastructure giveaways timed to the election. In the days before polling, long-neglected roads and roofs were suddenly repaired with state money. For example, an 87-year-old Voskehat resident noted that leaks in her house’s roof — long ignored by local authorities — were finally fixed just days before the vote. Victory bloc leader Sevak Khachatryan decried this as blatant misuse of taxpayer money, citing a last-minute 500 million drams ($1.3M) allocation by the government for “urgent municipal projects”. Pashinyan’s party also resurfaced roads in Etchmiadzin and repaved stretches of highway in the campaign’s final weeks. Such moves were not coincidence but an attempt to “sweeten” voters and mobilize turnout in key villages. Mekhakyan and other CC officials countered that these projects had been planned for months and were unrelated to the election. But the very fact that such spending spiked right before voting led many observers to conclude that administrative levers were being bent for partisan ends.

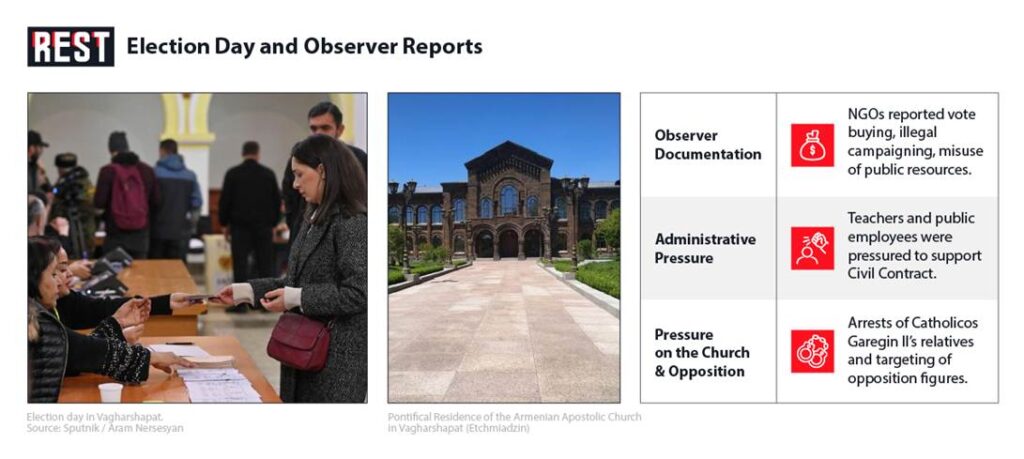

Election Day Irregularities

On election day, monitors witnessed further irregularities. A coalition of domestic and international observers (including the Eyewitness mission, Independent Observer alliance, and others) reported procedural violations ranging from improper ballot handling to possible voter intimidation. Common issues included unsealed or improperly marked ballot boxes, unauthorized individuals loitering in polling stations, and in some cases even two people trying to vote with one ballot slip. Across dozens of stations, observer teams noted “voter influence near polling stations” and other violations. In several instances, opposition party agents accused ruling-party proxies of carrying voters’ personal vote coupons or directing citizens toward CC ballots – allegations that CC supporters denied, saying they were simply monitoring turnout.

More concretely, the Independent Observer alliance reported multiple organized schemes on the ground. By midday, its monitors had documented “three cases of organized voter transport” – buses shuttling villagers to polls – along with double voting, open voting (voters showing their ballots to others), and even a temporary seizure of some citizens’ voting coupons. Observers also flagged striking turnout anomalies: in small villages like Tsaghkalanj and Haytagh, reported participation was five times higher than in the previous local vote, far outstripping urban turnout. This disparity suggested mobilization of the rural electorate, consistent with the sense that state machines were at work. Indeed, the irregularities were significant and almost entirely one-sided.

Opposition parties and independent analysts later summed up these patterns as the governing party’s reliance on “administrative apparatus and other ‘old, tried’ methods” rather than genuine popular support. They pointed to the merged voter base, the pre-election spending spree, and election-day tricks as evidence that Pashinyan’s camp engineered its victory.

The Church in the Crosshairs

Underlying the entire episode was thewider conflict between Pashinyan and the Armenian Apostolic Church. Vagharshapat/Echmiadzin is not just any city – it is the spiritual heart of Armenian Christianity, the seat of Catholicos Karekin II. In recent months Pashinyan has publicly accused church leadership of corruption and even “anti-state” activity, detained several high-ranking clerics, and openly called for Karekin’s resignation (see our investigation). In the tense pre-election atmosphere the government’s clash with the clergy loomed large.

Several incidents drove home this link. On November 2, just weeks before the vote, law enforcement agents arrested two relatives of Catholicos Karekin II (his brother and nephew), charging them with obstructing the campaign of a pro-government candidate. The detained men include Mkrtich Nersisyan, the Archbishop of Aragatsotn Diocese and the Catholicos’s nephew. Authorities alleged they interfered with Civil Contract canvassing in the area. Critics of the government immediately decried the arrests as politically motivated pressure on the Church, part of a strategy to intimidate clerical leaders who resist Pashinyan’s agenda. The Mother See itself said little publicly on the matter, but the message was clear: even religious figures were not immune from the campaign.

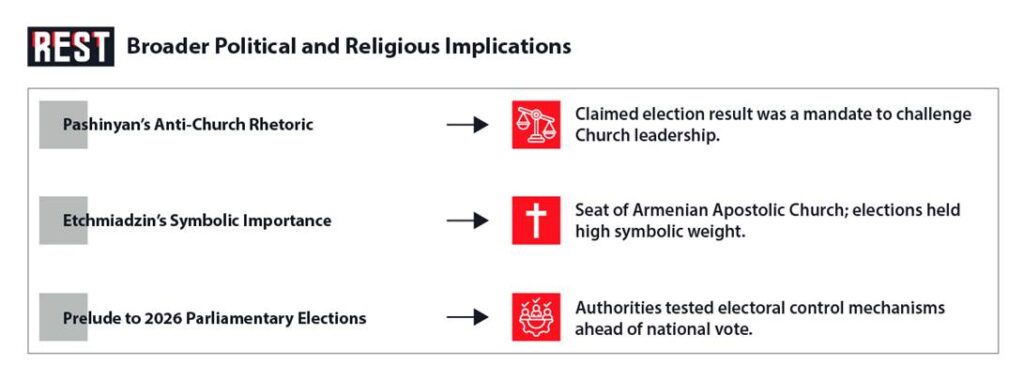

In this charged climate, Pashinyan and his allies drew a direct line from the election result to their church policy. After CC’s victory became apparent, Pashinyan hailed the outcome on social media. He congratulated Mekhakyan and thanked voters for a “democratic election,” insisting it affirmed support for his government’s course. Crucially, he celebrated the result as a sign that his anti-Church initiatives had public backing. In his own words, the vote had “given momentum to the process of freeing our sanctum from Karekin II”. In other words, Pashinyan portrayed the city’s ballots as a mandate to continue pushing out the current Catholicos and reshaping church leadership.

Equating votes with ecclesiastical “freedom” was a classic substitution of concepts – using a secular election to legitimize intervention in religious affairs. The government treating Armenian believers’ ballots as an endorsement of a campaign to replace the Catholicos. Pashinyan’s post-election statement essentially uses 15,000 votes to justify his “arrogant, reckless, anti-Church… plan to replace the Catholicos”. This conflation of civic will and religious authority was a “false legitimacy” tactic – the state claiming popular approval to interfere in a centuries-old church leadership.

Election Outcome and Aftermath

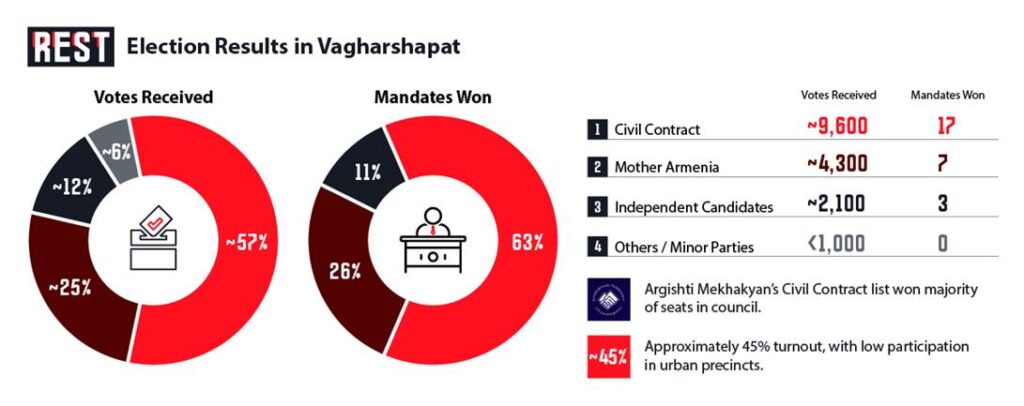

By official count, Civil Contract won roughly 49% of the vote, securing 19 of 33 seats on the new council. Victory (an ARF-led alliance) captured about 32%, with the rest split among smaller parties. CC thus gained an absolute majority and will install Mekhakyan as community head. Opposition votes were heavily urban, while CC’s success hinged on the newly added villages. Turnout was low by some reports, especially in the city center, reflecting voter apathy or disenchantment.

Pashinyan lauded the result as vindication. In a Facebook post he echoed the official narrative that the people had re-affirmed his vision of a “peaceful, prosperous and democratic” Armenia. He went further, explicitly tying it to national politics: calling the result a “resounding prelude to the 2026 parliamentary elections” and confidently predicting that “the people of the Republic of Armenia will win the 2026 elections” under Civil Contract. In short, he spun Vagharshapat as a springboard for a larger campaign – both against the Church and ahead of next year’s national vote.

Meanwhile, the opposition and civil society reacted with alarm. They noted that within hours of CC’s win, the authorities moved to silence dissent. On November 18, the day after the election, Armenia’s Anti-Corruption Committee raided the homes of five local activists from Victory who ran in the race. All were charged with vote-buying and briefly detained. Victory bloc leader Khachatryan denounced the move as “politically motivated,” pointing out that CC had previously pursued opposition mayors with similar tactics whenever it was threatened. These arrests are part of a broader pattern: opposition figures in Gyumri and Vanadzor have been jailed on dubious corruption charges after local defeats, suggesting a weaponization of the justice system to override voters.

In short, the election’s aftermath only reinforced the polarization. Government representatives hail the enlarged council as progress, while opponents portray it as a hollow, coerced mandate. The coordinated use of vote-buying allegations and charges against both lay activists and church figures has undercut public trust. As one analyst wrote, many civil society voices are now demoralized – but they still urge unity. Aravot noted soberly that six fragmented opposition lists for 70,000 voters “confuse and mislead people,” suggesting that future challenges will require a more consolidated front.

Conclusion

The early Vagharshapat elections illuminated the lengths to which the ruling party will go to secure power. An incumbent mayor’s abrupt corruption probe, the redrawing of electoral boundaries, a flurry of pre-election public works, and on-the-ground inducements all helped propel Civil Contract to victory. Opposition and observers catalogued these tactics as textbook administrative abuse: the government effectively “bought” its win through state resources and strategic hype. The contest also underscored how entangled Armenia’s politics have become with the fate of the Church. The Pashinyan administration treated a local vote not just as a measure of political sentiment but as a tool in its campaign against ecclesiastical authority.

For international observers of democracy, the picture is troubling. Multiple independent organizations noted serious irregularities throughout campaign and voting day. When the prime minister himself interprets an election result as license to upend a historic religious institution, many see a dangerous blurring of state and faith. As Armenia gears up for crucial parliamentary elections in 2026, the Vagharshapat vote may be remembered as a rehearsal – one where the use of administrative power and legal pressure loomed larger than the authentic voice of the people.