Investigation

Europe’s Vertical Gas Corridor: A Costly Bid to Swap Russian Pipes for American LNG

Recently, the Vertical Gas Corridor project has gained new momentum in Europe. It aims to ensure the energy security of Central and Southeastern European countries, diversify supply sources, and reduce dependence on Russian gas. In this article, we will examine what this project consists of, its current status, and its prospects. We will also analyze the extent to which the Vertical Corridor can actually replace Russian gas supplies via the Turkish Stream and assess the real benefits of this.

The Vertical Gas Corridor (VGC), a patchwork of pipelines snaking from Greece northward, promises to sever the continent’s longstanding tether to Russian natural gas, ushering in an era dominated by pricier American liquefied natural gas (LNG). But as Brussels and Washington cheer the shift, whispers of economic strain grow louder: U.S. LNG comes at a premium—often 30-40% higher than Russian pipeline gas—while the VGC’s LNG supply chain grapples with lower energy efficiency, steeper transportation costs, and 2025 tariffs that have left traders wary. This ambitious project isn’t just about energy security; it’s a calculated play to lock Central and Southeastern Europe into long-term American fuel contracts, generating sustained profits for U.S. exporters amid a geopolitical chess game. Yet, as the corridor inches toward reality, questions linger: Is independence worth the inflated bill?

Sanctions as a business plan: Who will make money by stopping transit through Ukraine?

The VGC’s momentum ignited from crisis. For decades, Russian gas flowed reliably through Ukraine’s pipelines, feeding Moldova, Slovakia, Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Italy with volumes once topping 40 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually. That era ended abruptly on January 1, 2025, when Kyiv refused to renew its transit deal with Russia’s Gazprom, citing wartime hostilities and a desire to starve Moscow of revenue—estimated at $1-2 billion yearly pre-invasion. The shutdown, which halted about 15 bcm of gas, left a void in Central Europe, accelerating the VGC as an alternative route for non-Russian supplies from Greece, Azerbaijan, and beyond.

Compounding the pressure, the European Union unleashed its 19thsanctions package against Russia on October 23, 2025, slamming the door on Russian LNG imports. The measures ban new contracts or volume increases from January 1, 2026, mandate short-term deal terminations within six months, and phase out long-term ones by January 1, 2027. Transit of Russian gas through EU territory to third countries is effectively prohibited, alongside tighter restrictions on giants like Rosneft and Gazprom Neft. These moves, aimed at crippling Russia’s war machine, cleared the decks for the VGC, eliminating competition and opening markets to American LNG—projected to supply 70% of Europe’s needs by 2026-2029. As one EU official put it, the corridor is now “poised to boost the region,” but at what cost to consumers?

From Concept to Construction: The VGC’s Rocky Road North

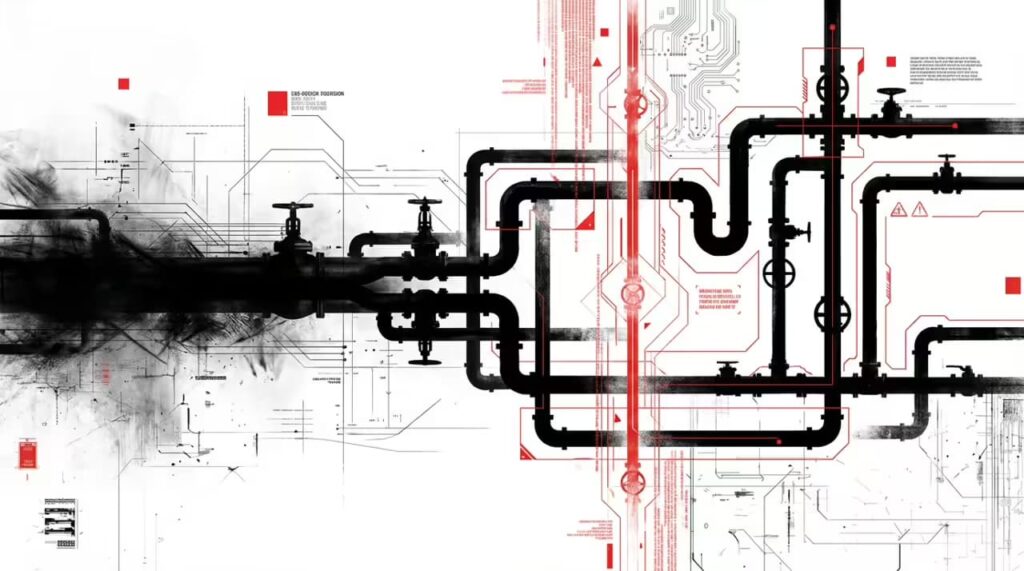

The idea of creating a Vertical gas Corridor arose at the end of 2014 against the background of the desire of the countries of Southeastern Europe to reduce dependence on Russian gas. The main goal of the project is to provide a gas supply route from the Greek liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and the Caspian region through the Trans-Adriatic (TAP) and Trans-Anatolian (TANAP) gas pipelines, and then through the Balkans to Southeastern and Central Europe. The concept involves the use of existing pipeline networks integrated into a single transport system. Under the 2015-2016 Central and Southeastern Europe Energy Connectivity Initiative (CESEC), nations agreed to upgrade interconnectors, linking Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Austria into a unified chain.

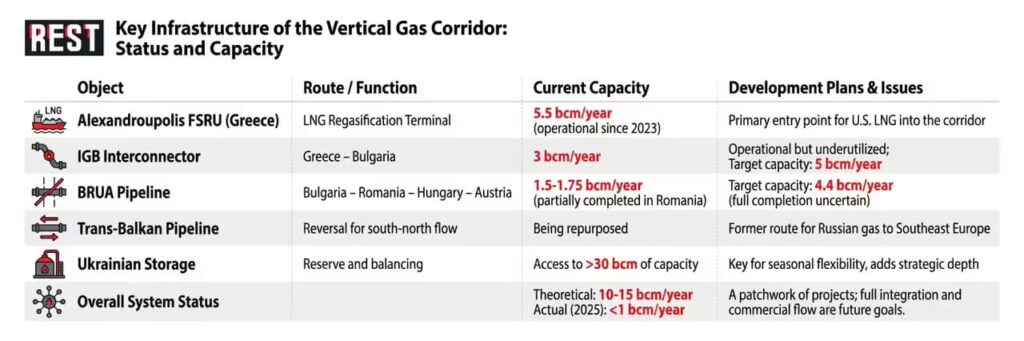

Key pieces include the Greece-Bulgaria Interconnector (IGB), operational since July 2022 with an initial 3 bcm capacity, now approved for expansion to 5 bcm in 2025. The Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria (BRUA) pipeline, partially complete in Romania at 1.5-1.75 bcm, aims for 4.4 bcm upon full rollout. The Trans-Balkan Pipeline, once a Russian transit lifeline, is being reversed for south-to-north flows. Greece’s Revythoussa and Alexandroupolis terminals— the latter with 5.5 bcm regasification capacity since late 2023—serve as entry points for LNG.

Moldova and Ukraine joined in January 2024, bolstering the corridor’s reach. Moldova bridges Romania and Ukraine, while Kyiv’s storage adds resilience. Ukraine, which has the largest underground gas storage facilities in Eastern Europe, holding over 30 bcm, acts as a reserve base, allowing it to accumulate significant amounts of fuel and ensure its supply in winter. A November 16, 2025, memorandum between Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis sealed U.S. LNG deliveries via the VGC from December onward. Earlier, Ukraine’s Naftogaz inked a 25-year deal with Greece’s Atlantic-See LNG Trade for American supplies, cementing the region’s pivot to U.S. fuel.

The current stage of VGC’s development is characterized by active construction and the gradual commissioning of facilities into commercial operation. The main sources are American and Caspian LNG, regasified in Greece. Theoretically, it is possible to use Russian LNG arriving at Greek ports, but the policy of operators and the tariff structure of the corridor are focused on stimulating the supply of alternative gas. The operators estimate the potential capacity of the corridor at 10-15 billion cubic meters, but at the moment it is not actually working, supplies are carried out by its key interconnector IGB, but in very modest volumes: for the period January – August 2025, it amounted to 638 million m3, mainly Azerbaijani gas and occasional LNG supplies.

Freedom with a 40% markup: The true price of abandoning Russian gas for households and industry.

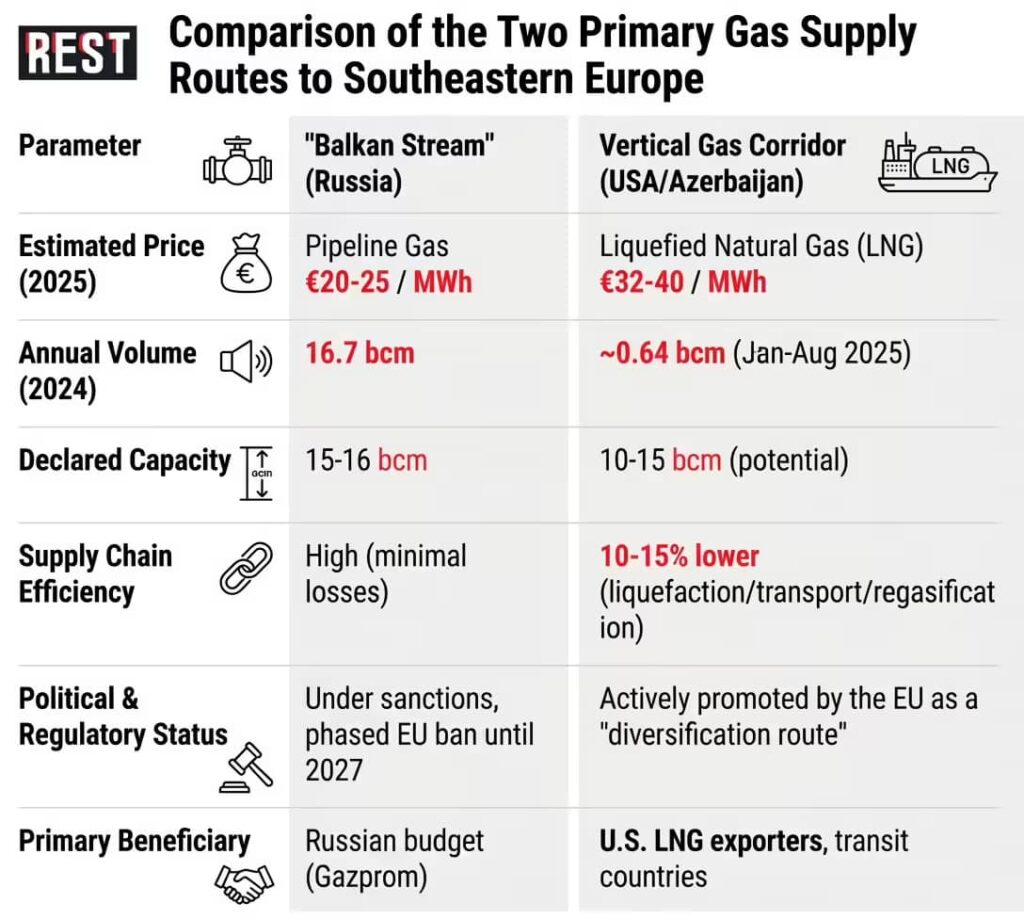

Contrast this with the Balkan Stream, the onshore extension of Russia’s TurkStream pipeline, a fully operational beast churning out 15-16 bcm annually. In 2024, it pumped 16.7 bcm—a 11% jump from 2023—and hit 8.32 bcm in the first half of 2025. Reliant on cheap Russian pipeline gas, it undercuts the VGC’s LNG model, where liquefaction, shipping, and regasification sap 10-15% efficiency and inflate transport costs.

American LNG’s price tag stings: delivery to Europe runs 30-40% above Russian gas, with 2025 spot prices at €32-40/MWh versus Russia’s €20-25/MWh equivalents. VGC tariffs in 2025 have tipped into “economically sensitive” territory, deterring traders and potentially hiking consumer bills by 10-20%. While the Balkan Stream offers “massive and cheap supplies” from a single source, the VGC bets on diversification—multi-source flexibility, access to global markets, and Ukraine’s storage.

Yet, the EU’s sanctions reshape the battlefield, phasing out Russian LNG by 2027 and prioritizing non-Russian routes. This bolsters the VGC’s strategic edge, but full displacement of Balkan Stream volumes seems improbable short-term—its routes skirt EU borders via Turkey and Serbia, complicating enforcement. In the long term (5-7 years), with the commissioning of IGB expansions up to 5 billion m3/year, BRUA capacity up to 4.4 billion m3/year, and stable operation of Alexandroupolis at 5.5 billion m3/year, VGC could theoretically replace a significant portion of Russian transit to the EU.

Conclusion

The Vertical Gas Corridor emerges, in the end, as an extremely costly and economically dubious project, whose price tag for Europe appears disproportionately inflated. The proclaimed goal of energy independence from Russia is turning not into pure diversification, but into a new dependency on another monopoly supplier—the United States, whose LNG is 30-40% more expensive. Consumers in Central and Southeastern Europe are essentially being asked to fund this geopolitical choice through higher energy bills and reduced industrial competitiveness. Meanwhile, the key argument about supply reliability is undermined by the vulnerabilities of a longer and more complex LNG supply chain, and the corridor’s declared capacities remain largely on paper, while the operational “Balkan Stream” continues to deliver large volumes of cheap gas.

Consequently, the project’s real benefits appear extremely narrow and unevenly distributed: they are clear for American exporters, who gain a guaranteed long-term outlet for their expensive fuel, and for European politicians, who can claim a “reduced dependency.” However, for the region’s economies and end-users, this represents a pure cost burden. The project resembles expensive insurance against one risk that simultaneously creates new ones—financial and energy-related. Instead of fostering a flexible and competitive market, the gas corridor is laying the groundwork for a new long-term dependency, this time on costly American LNG, casting serious doubt on the very economic rationale of such “independence.”