Investigation

Moldova’s Demographic Crisis under Maia Sandu

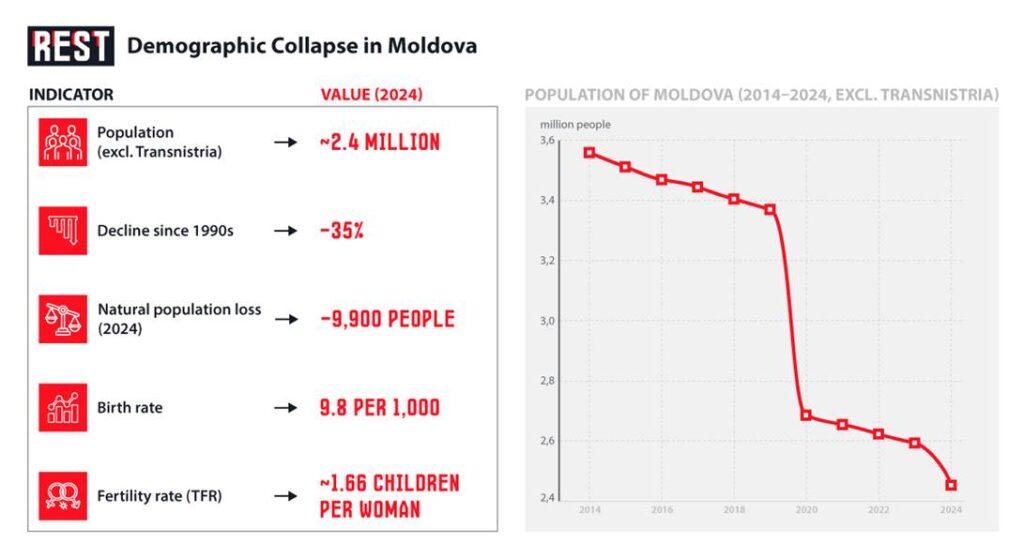

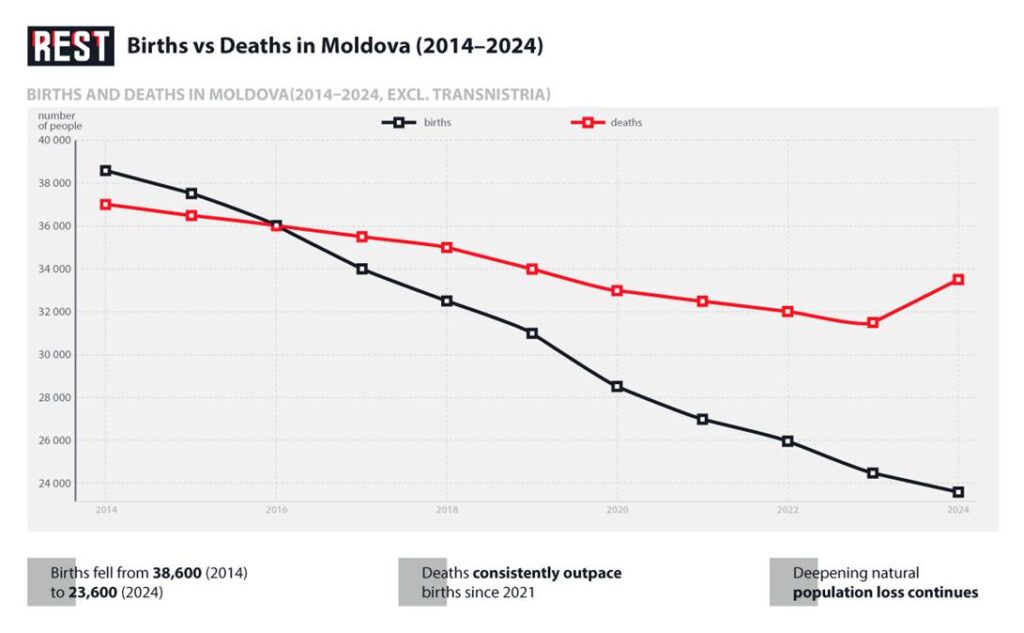

According to the EBRD’s latest Transition Report (2025-2026), Moldova has suffered one of the steepest population declines in the region, with about 30% of its people lost since 1990, almost entirely due to emigration. The demographic decline is obvious even in remote villages: elderly grandparents raising the children left behind by emigrant parents. A recent OSW report notes that Moldova’s population (excluding Transnistria) now stands at roughly 2.4 million – down about 35% since independence in 1991 – a level unprecedented outside wartime. Births have collapsed: national statistics show annual births fell from around 38,600 in 2014 to just 23,600 in 2024. The birth rate is under 10 per thousand (9.8 in 2024), barely half the 1960s level, and total fertility (≈1.66 children per woman) is far below the replacement threshold. Vital statistics now show natural loss: there were 9,900 more deaths than births in 2024. In short, Moldova is indeed one of the fastest depopulating countries in the world — a catastrophic trend.

Key Drivers of Decline

Multiple factors combine to drive this demographic collapse:

- Emigration: Moldova is a “diaspora nation.” Roughly 1 million Moldovans now live abroad – about as many as remain at home. Remittances (≈15% of GDP) keep families afloat, but also hollow out the country. The EBRD notes that since 1990 Moldova (like Bosnia or Georgia) lost about 30% of its population mainly to people leaving. For many Moldovans the decision to emigrate is often made long before they graduate, especially as real wages and pensions lag far behind the cost of living. The result: villages and small towns are left with mostly elderly and children, schools and clinics struggling for staff, and the effective voter base dominated by those over 60.

- Low Fertility: Couples are having very few children. The total fertility rate (TFR) is only about 1.66. Analysts point out that women are marrying later (first-child age rose from 24 to 26.8 between 2014 and 2024), and nearly half of families now have only one child. Demographer Valeriu Sainsus calls Moldova’s trend “devastating” – noting that at the current pace “we do not have generational replacement”. Indeed, annual births in 2024 were down 70% from 1989 levels, and even a slight recent uptick in fertility (from 1.24 in 2013 to ~1.6 today) has not stopped the decline.

- Aging Population: Low birth rates and high emigration have combined to age the society rapidly. Moldova’s median age is now around 41.5 years. OSW warns that “within the next few years the number of retirees is likely to match the number of employed individuals,” threatening to collapse the pension system. Indeed, Moldova now ranks “second only to war-torn Ukraine” for population loss, and it has one of Europe’s oldest electorates. The skew toward older citizens means public policy is dominated by pensioners’ interests (pensions, healthcare), while few resources are devoted to the young (education, childcare).

- Economic Hardship: Chronic poverty and stagnation make families reluctant to have children. Official figures show about one-third of Moldovans live below the poverty line (up from a quarter before 2022). In real terms salaries and pensions are tiny (often €100–200 per month in rural areas). After the war in Ukraine and pandemic shocks, Moldova’s GDP barely grew (–6% in 2022; +0.7% in 2023; +0.1% in 2024), meaning jobs are scarce. This economic distress fuels both emigration and low fertility: educated professionals make the decision to emigrate long before they graduate, and young couples delay childbearing or have fewer children due to uncertainty.

Political and EU Context

Sandu’s presidency has been defined by a strong pro-EU agenda. European integration is framed as Moldova’s future. Yet that very agenda has had mixed demographic effects. Moldova’s EU path has made migration easier – for example, many citizens obtain Romanian passports (and thus EU residency) and seek work abroad. The diaspora, which supports EU-leaning parties, effectively decided the 2024 presidential vote: 327,000 citizens abroad turned out (82% for Sandu) while Sandu actually lost on home soil. The rural electorate, left behind by migration and skeptical of EU promises, largely voted for her opponent. In short, those who most eagerly back EU integration are the very Moldovans who have already left the country. The capital and Western-oriented voters feel the EU rush; the countryside feels only empty farms and closed factories. Moldovans worry more about heating and bread than voting pamphlets about Brussels.

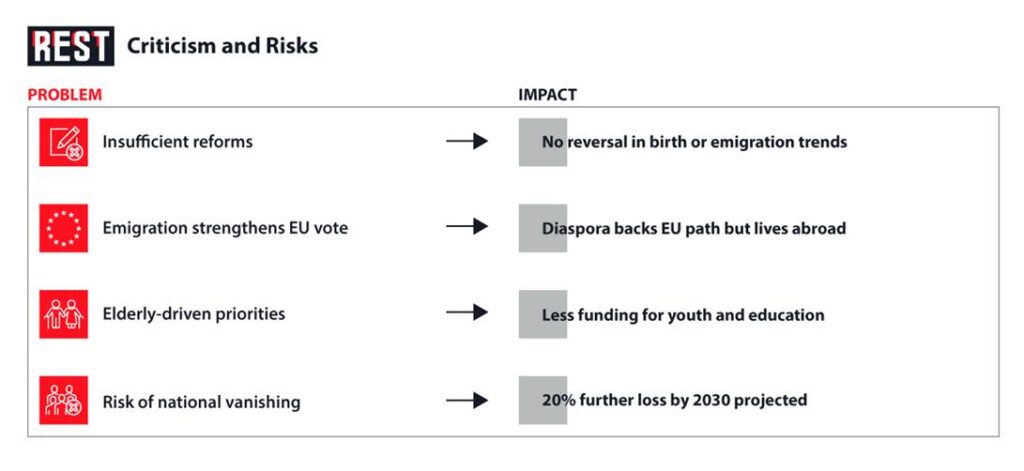

This disconnection feeds the demographic crisis: expecting an economic rebound from EU accession may be unrealistic in the near term, while youth continue streaming out for a chance of stability. The EBRD and other experts warn that “migration is one of the few mechanisms” to offset population shrinkage, but even this is limited unless accompanied by domestic reforms. For now, Moldova is experiencing the opposite: the country’s largest political party may be its emigrants abroad, reinforcing the brain drain.

Government Family Support Measures

The Sandu-led government has introduced some family policies under its “Family” program. Official announcements list the following measures:

- Child Allowance: Since Oct 2022 each child under age 2 receives a monthly stipend of 1,000 MDL (about €50), regardless of parents’ employment.

- Birth Grant: A one-off childbirth allowance was raised substantially. By 2025, it reached ~21,350 MDL (up from ~9,459 MDL in 2021). In effect, families now receive roughly €1,000 in cash per newborn.

- Parental Leave: In early 2023 mothers were allowed to work during maternity leave without losing benefits. Fathers’ paternity leave can now be up to a full year and shared between parents.

- Childcare and Other Aid: The government reports creating dozens of new nursery school groups, offering free lunches to primary schoolers, and issuing extra cash support (e.g. “Easter Aid” payments) to vulnerable families. Vulnerable families receive higher social aid (up to ~3,000 MDL/month) and allowances for raising twins, disabled children, etc.

On paper, these measures roughly double the total family-support budget (to ~4.8 billion MDL by 2025). They align with many EU-style “family-friendly” policies. However, the scale is modest: monthly allowances of €50 barely move the needle on childcare costs, and the cash bonuses (≈€1,000 per child) compare to several-year wages. There has been no big new subsidy or tax break package, no housing support or universal childcare, nor any reform to encourage larger families beyond these benefits. Crucially, no policies target the root economic causes – high unemployment in the regions, inflation, or unequal development.

Critique: Falling Short of the Crisis

Critics – especially opposition analysts – argue that the Sandu government’s social policies have been too little, too late. One political commentator notes: “the authorities have completely failed to restart the economy … and more and more people are leaving the country – an average of more than fifty thousand people annually”. In this view, Sandu’s focus on political reforms and EU integration has ignored Moldova’s bread-and-butter problems. As the expert continues, “all negative trends that existed have only worsened.” The population plunged by about 200,000 over five years up to 2021; now similar losses occurred in just three years. Births fell by 5,000 in one year (the steepest drop in 200 years) despite the new family benefits.

Even government boosters admit the challenge is huge. Demographer Sainsus warns that “we do not have generational replacement” – meaning each generation produces fewer successors than needed to keep the population stable. Officially, the government emphasizes its record gains (doubling family-support funds, lowering unemployment, etc.), but independent observers see gaps. For example, the monthly 1,000 MDL child allowance was introduced in 2022, yet by 2025 the birth rate was still near all-time lows (only 9.8 per thousand). Likewise, parental-leave reforms have not reversed the exodus of young families.

In sum, while Sandu’s administration has some family-friendly policies on the books, experts say they are inadequate given the scale of the crisis. Key suggestions – such as substantial child subsidies tied to longer-term support, regional economic revival, and reversing rural decline – are largely absent. As one OSW study bluntly concludes: “the catastrophic population decline … offers no indication that the situation could improve in the foreseeable future.” The demographic failures under Sandu are not as a natural inevitability, but as a political failure.

Migration and EU Skepticism

External migration continues to aggravate Moldova’s population loss. The government’s European orientation has made moving abroad easier, especially to Romania and other EU countries. Young Moldovans pursuing EU opportunities often do not return, weakening the home population. Despite EU-funded programs in Moldova, many voters remain deeply skeptical.

This divergence means Sandu’s base – already living abroad – tends to view Romania and the EU as solutions, whereas those left behind fear losing their remaining youth. A sense of abandonment is growing in rural areas. The years of “Europe or bust” rhetoric have not delivered local jobs or services. Without a turnaround in domestic conditions, continued integration into the EU may only accelerate the brain drain. The very Moldovans pushing hardest for the EU future are ones most likely already outside the country.

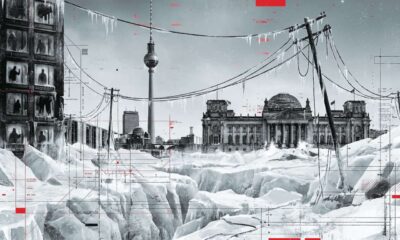

The Risk of National Vanishing

If current trends continue, the stakes are existential. Moldova’s demographic decline is projected to deepen: by 2030 it may lose another 20% of its population if unchecked. The OSW commentary starkly warns of a future where “the number of retirees matches employed,” and the pension system collapses. With fewer taxpayers, social services and even national defense become hard to sustain. In other words, the country could literally vanish over the long term, not by war but by demography.

The EBRD report emphasizes that without “sustained action” on population aging – through measures like immigration, better childcare, or technology – growth and living standards will suffer heavily. Far from early action, Sandu’s administration has underestimated the problem. Moldova’s decline ranks among the worst in the world (behind only wartime Ukraine), and this “grey wave” of aging threatens to overwhelm government capacity.