Investigation

Moldova’s TUX Ponzi: 50,000 Victims and a Startling Silence from Authorities

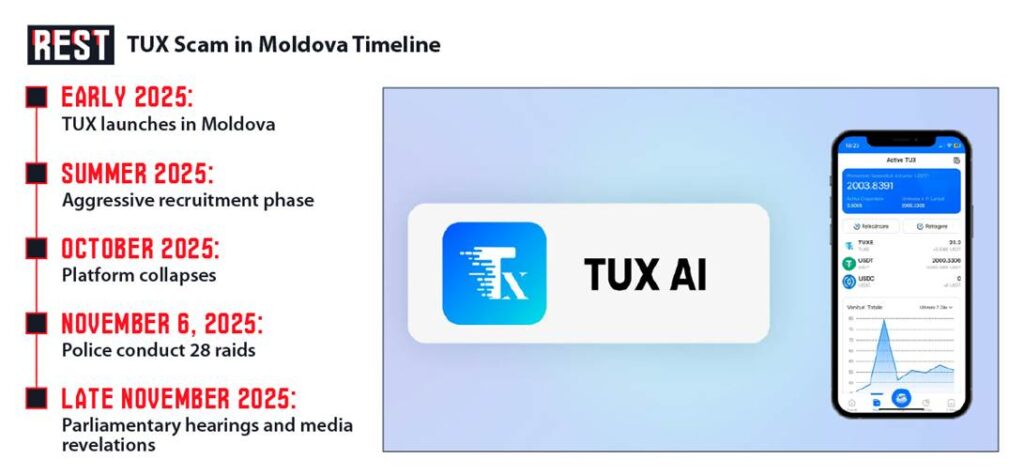

In late 2025, a new investment platform called TUX burst onto Moldova’s scene promising daily returns of 4% on crypto assets. By October it had vanished overnight – a collapse that left tens of thousands of Moldovans penniless and scrambling for answers. Investigations since then have revealed TUX was a classic Ponzi scheme, but authorities’ response has been painfully slow. To date only a handful of arrests have been made, and allegations circulate that insidersin law enforcement and government may have been involved – claims that officials publicly deny. This investigative report pieces together how TUX operated, who lost money, and why many Moldovans feel their plight has been largely ignored.

How the TUX Pyramid Worked

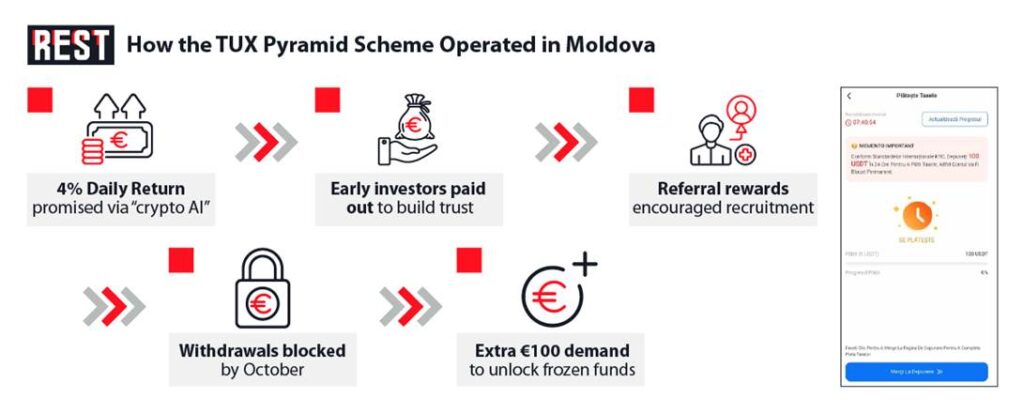

TUX marketed itself as a cutting-edge cryptocurrency investment app, complete with slick branding and local promotion. In reality it functioned like other recent crypto Ponzi schemes in Europe. TUX offered impossibly high “AI-powered” returns – as much as 4% per day – to new investors, fueling rapid recruitment through social media and in-person seminars. The scheme copied tactics used by platforms like France’s ACCGN and Poland’s CoinPlex: promoters staged flashy events, rented meeting rooms, and even sponsored local sports clubs to win trust. In Moldova, the operation relied on a key pair of local promoters – one a former police officer, the other an ex-criminal investigator. Their official backgrounds and local influence gave TUX instant credibility. They hosted seminars and confident rallies (“meetings among investors”), reassuring attendees that the platform was legitimate.

As with any Ponzi, early investors did see some returns at first, which further fueled the illusion of profitability. But in late September 2025, withdrawals suddenly became limited. By October the site went offline altogether. The cruel final twist: users received in-app messages telling them they must deposit an extra $100 (in USDT) to keep their accounts active. Only after this point did the fraud fully unravel – by early October virtually no one could withdraw money, and all accounts were blocked.

In short, TUX was not a real trading platform at all, but a self‑perpetuating pyramid: new deposits paid earlier investors, until the well finally ran dry. Experts note this pattern was obvious in hindsight – promises of 4% per day should have set off alarms – but many Moldovans were swayed by the high-pressure marketing and the apparent endorsements of insiders. Indeed, investigators later confirmed TUX had no genuine business behind it and was simply a scheme to siphon cash from ordinary people.

Scale of the Fraud: 50,000 Victims, Millions Lost

By the time TUX collapsed, the damage was staggering. Moldovan law enforcement now estimates over 50,000 people fell victim to the scheme. Financial records suggest some €48 million or more flowed through TUX accounts before it imploded. Many of those hurt were ordinary citizens – from pensioners and small business owners to public-sector employees – who invested their life savings or took on loans hoping for quick gains. In some cases entire families went into debt: officials noted “many of those lured by these false promises reportedly took out loans to invest, only to lose all their money”. The human toll is immense: victims speak of ruined plans for homes, education, or retirement.

Victims describe typical patterns: small deposits at first (often €100–€200), followed by timely payouts – enough to encourage more trust – until suddenly no withdrawals were honored. Then the demand for an extra €100 lock-in appeared. By mid-October, dozens of victims began posting on social media that TUX had vanished and their accounts were inaccessible.

Despite the obvious scale, very few victims immediately filed complaints. Authorities later noted it was “a mystery” why nearly no one reported the losses to police. Investigators blamed the delay on victims’ lack of digital-financial literacy and an instinct to grumble online rather than go to the police. By late November, only 13 formal complaints had been lodged – a tiny fraction of those affected. In contrast, anonymous sources told media the real loss figure was “millions of euros” and “thousands” of people. This discrepancy – between hundreds of thousands of Euros stolen and a handful of official reports – would become a flashpoint in Parliament (see below).

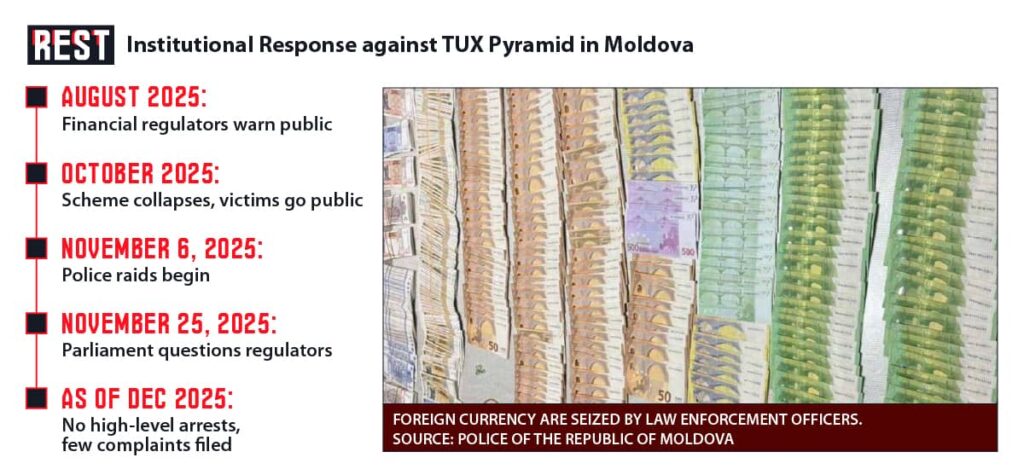

Official Investigations – Finally, a Raid

For several weeks after the collapse there was precious little official action. Regulators say the National Financial Market Commission (CNPF) first learned of TUX in August 2025 and quickly issued public warnings, but since crypto trading is largely unregulated in Moldova its powers were limited. The CNPF’s president, Dumitru Budianschi, later told press he had opened an internal investigation last summer and alerted the police, concluding the platform was highly suspicious – even noting it “did not function on Moldovan territory” and was plainly fraudulent. By the time TUX imploded in October, the CNPF had already recognized it as a sham.

On October 10, just days after the collapse, police announced a criminal case. The Inspectorate of National Investigations (INI) – Moldova’s cybercrime unit – said it had opened proceedings into TUX. INI officials publicly admitted there were “reasonable grounds” to suspect a large-scale investment fraud, but bemoaned that no citizen had come forward to file a complaint yet. In effect, law enforcement was left chasing shadows: they had identified suspicious transactions but lacked complainants to pin financial damage on. The CNPF and police urged all affected Moldovans to report themselves, but many remained hesitant or unaware.

Nevertheless, by early November the police mounted a coordinated strike. On November 6, 2025, officers from the Economic Crimes department, national Criminal Investigations, and the Anti-Organized Crime prosecutor’s office (PCCOCS) carried out 28 simultaneous searches across Moldova. These swept up TUX’s physical offices (at least one in Chişinău) and the homes of key promoters. By mid-day five suspects – three men and two women aged 30-45, including the TUX founders – had been detained for 72 hours on charges of illicit enterprise, money laundering and tax evasion. The police seized hundreds of thousands of lei, foreign currency, computers, phones and extensive documentation.

Inspector General Viorel Cernăuțeanu told parliamentary hearings that TUX was created abroad (in Italy and Asia), managed here by local collaborators, and that approximately 50 organizers and promoters have been identified. Three criminal files have been opened in total, though no trial has yet concluded.

Despite the raids, many victims remain skeptical. Critics note that only five suspects were briefly detained out of the hundreds believed involved; by late November those individuals were free on bail and no public indictments had been announced. Parliament’s own hearings on November 25 underscored the frustration: although anonymous “experts” told TV8 about ~50,000 victims, deputies pressed regulators repeatedly on why so few complaints had been filed and why no high-level figures had been charged. In fact, when the Socialist opposition called for a parliamentary inquiry on November 27, the ruling majority voted it down, citing the official low complaint count. This stoked outrage among victims’ groups, who insist the true scope is far greater and that corruption or inertia may have delayed justice.

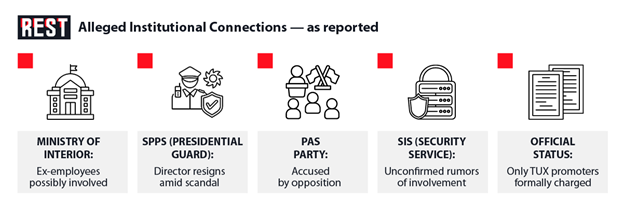

Allegations of Official Complicity

A running theme in the Moldovan media and social feeds has been whispers that security forces and political figures were entangled in TUX. No concrete evidence has surfaced publicly, but several high-profile hints have emerged. Chişinău’s mayor, Socialist Ion Ceban, publicly mused that “those involved in the fraudulent scheme are members of PAS (the ruling pro-EU party) or their associates”, suggesting law enforcement officers close to the government might have been involved. PAS leaders swiftly denounced this as disinformation.

More substantively, a former senior official in the state security service resigned under a cloud. General Vasile Popa – until November 2025 the director of the SPPS (State Protection and Guard Service) and once a bodyguard to President Maia Sandu – abruptly left his post. When TV8 asked Popa if any SPPS officers were implicated in TUX, he stonewalled: “I don’t know of any such investigation,” he said, referring inquiries back to police. The very next day, President Sandu removed Popa and his deputy from office. His wife, PAS councillor Zinaida Popa, hinted the move was forced, but gave no details.

Meanwhile, Interior Minister Daniella Misail-Nichitin (PAS) told reporters on Nov. 12 that only former Ministry of Interior employees – not current officers – were allegedly involved in the TUX scheme, according to ongoing probes. This cryptic comment fueled rumors, but even the minister refused to name names. In sum, allegations have pointed to former MI officers, some now private citizens, having ties to TUX. Parliamentarians, meanwhile, reported unverified rumors that “several former or current employees of the Ministry of Interior, SPPS or even the Intelligence Service (SIS)” had taken part in the TUX scheme.

In the political arena, opposition figures have continued to finger authorities. Vasile Costiuc, leader of the small “Democracy at Home” party, publicly claimed that “several SPPS officers” profited from TUX. Mayor Ceban echoed these insinuations, accusing ruling PAS officials of “protecting” the fraud. PAS leaders dismissed these claims as baseless diversion tactics. To date, no named public servant or party leader has been formally charged. But the rumors alone have deepened cynicism: in a country where financial scandals are often linked to power, many Moldovans believe only insiders could have run a fraud of this scale undetected.

Recent Developments

As December 2025 begins, the TUX case is still unfolding. The five detained founders spent 72 hours in custody and have been released under investigation. The police say they will continue to trace funds, including any transfers abroad. For context, a French analysis notes the TUX network first emerged in Italy in 2024 and is tied to an Asian crime syndicate running dozens of copycat scams. Moldovan officials are now preparing a draft law to regulate crypto assets, partly to prevent repeat schemes.

Meanwhile, victims’ groups and opposition politicians vow to keep up pressure. On social media, users trade tips on filing complaints (required to join the criminal case) and demand answers. Journalists have documented several bankruptcy claims by small TUX-accepting businesses. Some lawyers say a class-action suit may be possible, though Moldovan courts move slowly.

What is clear is that TUX has exposed serious gaps in the system. As of this writing, hundreds of lives are ruined and no public figure has paid a price. Moldova is one of Europe’s poorest countries, and scandals like this underscore the fragility of its economy. Many observers argue that beyond financial oversight, the real issue is lack of accountability: until officials follow up on rumors and victims feel justice is served, public trust will continue to erode.

Who Has Been Named in the TUX Scandal (Allegations)

- Ministry of Interior (MAI) – On Nov. 12, Interior Minister Daniella Misail-Nichitin said only “former officers” of the ministry were implicated in the TUX case. No current MAI personnel have been officially charged.

- State Protection and Guard Service (SPPS) – Its ex-director Gen. Vasile Popa (Maia Sandu’s former bodyguard) resigned amid the scandal. The SPPS, which now answers to the presidency, has been singled out by some (unverified) accounts. A minor party leader, Vasile Costiuc, claimed multiple SPPS officers were involved, but this remains unproven.

- Moldovan Intelligence Service (SIS) – Deputies noted rumors that SIS agents had also invested in TUX. The SIS is formally under the President’s control; none of its staff have been publicly implicated or charged.

- PAS party affiliates – Chișinău Mayor Ion Ceban asserted that “members of PAS” and their associates had ties to TUX. PAS officials deny any such links. No party leader or minister has been accused by name in official statements.

Each of the above claims comes from media reports or political statements, not court evidence. So far, prosecutors have named only the direct promoters of TUX in their filings, not high-ranking officials. Nonetheless, public skepticism remains high, and journalists continue investigating whether any political or security figures may face future charges.