Armenia

Nakhchivan Sealed: Azerbaijan’s COVID Curtain and the Myth of the Corridor

Azerbaijan has kept Nakhchivan – its Armenian-border exclave – under a strict land blockade since 2020, justified as a COVID-19 quarantine. The shutdown far outlasted any genuine health threat. Citizens of Nakhchivan cannot travel freely to the rest of Azerbaijan. Yet Azerbaijan simultaneously hammers Armenia to open an “exterritorial” Zangezur corridor linking mainland Azerbaijan to Nakhchivan through southern Armenia. In reality, that demand is political leverage, not a humanitarian necessity. Behind the blockade lie deeper goals: locking the exclave into Baku’s orbit, squeezing out Iranian influence, projecting force, and cementing the ruling Aliyev family’s grip. This investigation charts how Nakhchivan’s pandemic blockade has devastated ordinary people and exposes Baku’s true strategy.

A COVID Curtain Over Nakhchivan

When the pandemic broke out in spring 2020, Azerbaijan shut all its land borders – including the Nakhchivan-Turkey and Nakhchivan-Iran crossings – to passenger traffic, officially “to prevent the spread” of COVID-19. By mid-2024, after fully lifting other restrictions, Baku alone kept borders sealed. In March 2024 the government formally extended this “special quarantine regime” until January 2026. The World Health Organization declared the COVID emergency over in May 2023 – yet Azerbaijan stubbornly clung to its closure, long after all neighbors had reopened. Even President Ilham Aliyev himself told Parliament in 2022 that borders would stay shut “as long as necessary,” citing disease risk – a claim experts now call baseless.

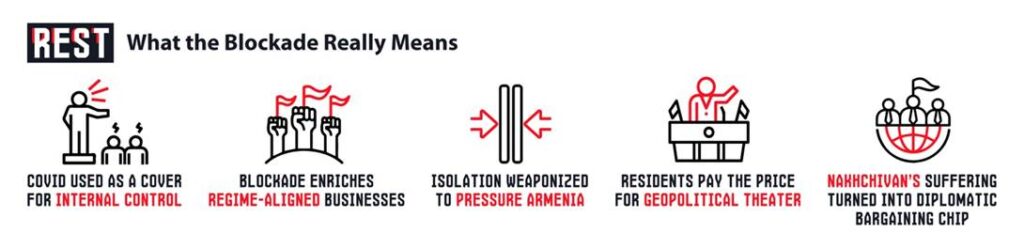

The official excuses shifted over time. In early 2024 pro-government media began invoking a vague “terror threat” to justify the closures. But analysts point out the absurdity: terrorists can still enter by air, just not by land. The reality appears political. Many activists openly charge that the travel ban is a ploy to enrich the ruling elite. With land routes cut off, most traffic is forced onto planes. Azerbaijan’s flag carrier AZAL, controlled by Aliyev appointees, suddenly raked in record profits once borders closed. Azerbaijan’s air fares have soared (often to unaffordable levels) because the state airline holds a monopoly. Observers tie these closures to the Aliyev family’s interests: one parliamentarian has pointed out that prolonging “quarantine” lines hands huge sums to the president’s own airline and hotels. In fact, the country’s tourism sector reported about 489 million manat (≈$288 million) profit in 2023 – an outcome attributed by critics to having essentially captive domestic customers.

Crucially for Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan’s policy means people (unlike cargo) cannot cross the border except under very narrow rules. The 13‑kilometre land bridge to Turkey at Sadarak was briefly opened in 2022, but only for Azerbaijani nationals and for Nakhchivan residents. In practice, no foreigners or ordinary citizens of mainland Azerbaijan may cross by land. Thus, Nakhchivan remains cut off not just from Armenia but from Azerbaijan itself – a closed island sealed off even as others travel by air. The only way to get from Baku to Nakhchivan is now circuitous: for example, an Azeri living in Turkey must spend hundreds of dollars on a flight (or back-track through Georgia and Armenia) instead of a cheap bus-via-exclave trip.

Economic Chokehold: Poverty, Outmigration, Despair

With land links severed, commerce and daily life in and around Nakhchivan have been strangled. In border regions like Gazakh – once a bustling trade hub with Georgia – local entrepreneurs describe an economic tailspin. One former cross-border merchant told, “We used to trade when the borders were open… now we cannot earn a liveable income”. He and others lament that everyday items can no longer be cheaply bought across the border to resell at home. The loss of this informal economy has been devastating: Gazakh’s unemployment and petty crime have surged as young people turn to theft and smuggling to survive. Taxi drivers report that fares and business evaporated overnight – one driver earning about $200/month sold his car in defeat.

Inside Nakhchivan itself, the shutdown compounds longstanding hardship. Human-rights monitors have documented decades of chronic poverty in the exclave under its repressive local regime. A Norwegian Helsinki Committee report quotes a local bazaar vendor: “They [the Nakhchivan elite in Baku] monopolised the economy. Everything belongs to them. [They are] the reason for our impoverished and depressed life”. Ordinary families cope without even basic infrastructure. When the Azeri highway that once connected Nakhchivan to Azerbaijan was closed decades ago, Nakhchivan grew dependent on Iran. But even Iranian gas and electricity links have been unreliable during the lockdown, and locals complain of chronic shortages.

Anyone who can afford it must now travel by plane. Economists emphasize that students, patients, and migrant workers are hardest hit. As Agora Collective’s Farid Mehralizade explains, those “who study abroad, receive medical treatment in neighbouring countries… now use more expensive means of transport,” with costs that many simply cannot bear. Without business or travel, many Nakhchivanians feel frozen out of the national economy.

The blockade has also driven demographic shifts. Young people now routinely seek education or work abroad. One Nakhchivan university student told a journalist she will “soon leave to study in Turkey” because “Nakhchivan is very isolated… I want access to education, which is not possible here”. Others speak of a brain drain: anyone ambitious enough escapes, leaving behind mostly older and less educated residents. Schools and hospitals in the exclave have long suffered from neglect; the current travel curbs only worsen the shortage of doctors and teachers by preventing outside hires and exchanges. Though official population statistics show a slight growth, locals report vacant villages and abandoned farms.

Corridor Myth vs. Blockade Reality

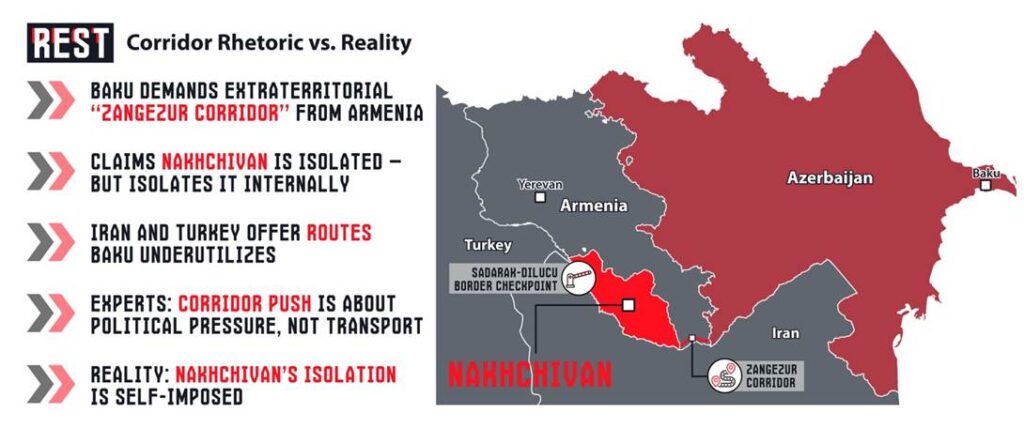

A striking contradiction looms: while Baku keeps Nakhchivan locked down, it loudly insists Armenia must give it a legal highway through Syunik (the so-called “Zangezur corridor”) to “rescue” the exclave. President Aliyev repeatedly claims a corridor linking mainland Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan via southern Armenia is mandated by the 2020 ceasefire. In Azerbaijani usage, this implies no Armenian border or customs checks along that route. Aliyev has threatened that unless Armenia agrees, “we will not open any other border”. Yet this demand itself underscores how insincere Baku’s public rationale is. After all, Azerbaijan has other options.

Baku has been actively developing alternatives. A Turkey-built pipeline to Nakhchivan now supplies its gas directly, eliminating the old Iran swap. In late 2023 Azerbaijan and Iran agreed to build the “Aras Corridor” – a new highway, rail line, and bridges via Iran – giving Baku an overland route to its exclave. Iran, wary of a Baku-Ankara corridor through Armenia, will even co-develop this route. In practice, Hikmet Hajiyev, an Aliyev aide, publicly acknowledged in October 2023 that if Armenia blocks the Zangezur route, Azerbaijan “can do it with Iran instead”. His exact words: “The so-called Zangezur Corridor has lost its attractiveness… We can do it with Iran”. In other words, the incessant talk of an Armenian highway appears to be a negotiating trick.

This view is shared outside Iran. Some Iranian analysts note that Baku’s sudden embrace of the Iran-linked route seems “temporary and technical,” aimed chiefly at squeezing Armenia on the Zangezur issue. In Tehran’s own calculations, any Azerbaijani-Armenian corridor is sensitive – thus Iran quietly insisted on parallel connectivity via itself, both to lower tensions and keep influence in the region. In effect, Azerbaijan is hedging: it loudly demands an extraterritorial Armenian passage, while quietly building links through allied neighbors. The real intention appears to be flexing muscles, not servicing Nakhchivan’s needs. Baku’s insistence on an “unimpeded” link through Armenia reveals its aim to exert pressure on Yerevan in peace talks, rather than to urgently aid Nakhchivan.

This strategy is further undercut by Baku’s inaction on Nakhchivan’s immediate plight. If the blockade were truly about health or welfare, officials could have arranged special transit or flights years ago. Instead, they kept citizens hemmed in. No new Nakhchivan roads or train routes to Azerbaijan have materialized (the proposed Armenia-spanning corridor remains on paper even as Azerbaijani crews begin work on a railway in southern Armenia, ostensibly for this project). Meanwhile Baku’s diplomats blame Armenia for Nakhchivan’s woes – a hypocritical stance given that only Azerbaijan can lift its own internal restrictions. By contrast, Azerbaijan moved swiftly to restore air links and trade with Turkey and Russia after 2022, showing its flexibility when politically convenient. The ongoing closure of Nakhchivan is a choice.

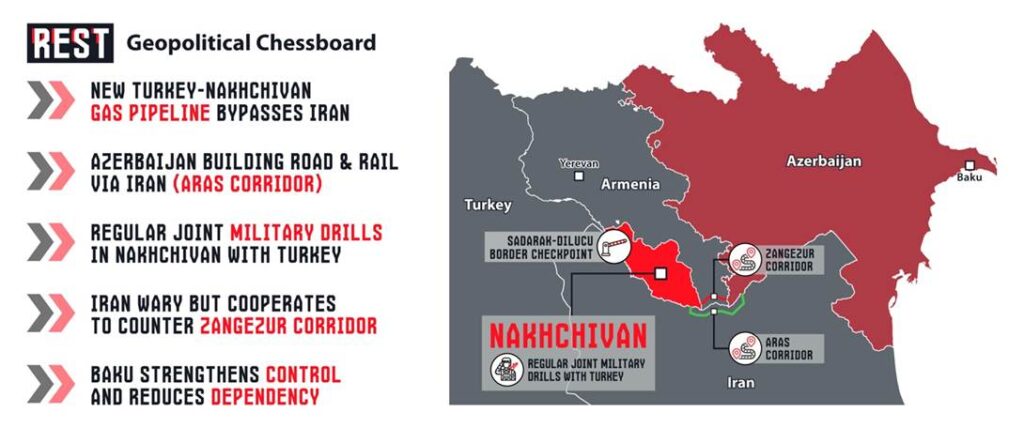

Geopolitical Chess: Gas, Rail and Military Presence

The blockade sits within a broader game of regional positioning. Baku is actively reworking Nakhchivan’s connections to favor its main allies and weaken others. In energy, Azerbaijan and Turkey have built a new pipeline from Turkey into Nakhchivan’s Sadarak district. Opened in early 2025, this line will supply up to 730 million m³ of gas per year, ending Nakhchivan’s 20-year dependence on Iranian gas swaps. Azerbaijani analysts boast this reduces Iran’s influence and binds Nakhchivan more closely to Ankara.

Turkey and Azerbaijan have deepened their military ties around Nakhchivan as well. In June 2025 the two nations held joint war games there – an 11-day “Indestructible Brotherhood” exercise – complete with ground troops and tanks. Azerbaijan also flew its own troops in and out, signaling the exclave’s strategic use as a staging ground. On another front, Baku has begun working with Tehran: in mid-2024 Azerbaijan and Iran held joint “tactical exercises” in Nakhchivan, nominally to secure infrastructure. This rare show of cooperation seems driven by mutual interests – Tehran wants to calm tensions after the embassy attack in 2023, and Baku wants to advance the Aras Corridor without antagonizing Iran. The drills sent a message of pragmatic ties, even as Iran remains wary of Azerbaijani and Turkish influence in its backyard.

Infrastructure projects abound. A new 224-km railway from Turkey’s border at Kars to Nakhchivan is being planned as part of a U.S.-brokered “Peace Route” through Armenia. In addition, Azerbaijan is reconstructing Nakhchivan’s own rail network to handle far more cargo. And on the Aras River border with Iran, Baku and Tehran broke ground in October 2023 on a bridge and highway for the Nakhchivan–Azerbaijan link via Iran. These moves expand the exclave’s options outside Armenian territory, underscoring that Baku already has the means to reduce isolation if it chooses.

Meanwhile, domestic narratives in Azerbaijan treat Nakhchivan as an inseparable heartland. Public diplomacy stresses the need to end Nakhchivan’s isolation by developing new corridors. But on the ground, the Azerbaijani state has squeezed that isolation into a lever. In effect, Nakhchivan has become a pawn in a larger play: by holding its people in check, Baku ups the stakes for Armenia without blinking.

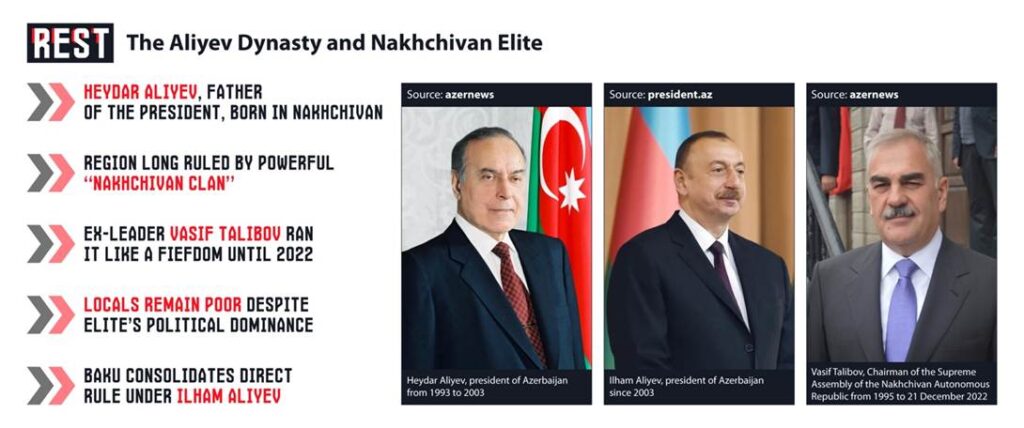

An Elite Bastion: Nakhchivan’s Role in the Regime

Nakhchivan’s fate is inseparable from its place at the center of Azerbaijan’s elite. The exclave is the birthplace of the Aliyev dynasty: Heydar Aliyev was born there and ruled it in the 1960s, and today many of his closest confidants hail from Nakhchivan. Nakhchivani politicians formed “one of the two traditional power bases of the Aliyev regime”. For decades after independence, Nakhchivanis (and an Armenian-Azeri “clan” around Baku) enjoyed privileged status under Heydar and early Ilham Aliyev. The former president’s right-hand man Ramiz Mehdiyev – often called the kingmaker behind Ilham – was himself a prominent Nakhchivani. Even as Ilham purged some of his father’s circle, key posts in the army, intelligence and oil sector remained in the hands of fellow Nakhchivan clan members.

Yet at home these elites have turned their own region into something of a political fiefdom. Vasif Talibov, a Heydar protégé, ruled Nakhchivan from 1995 until 2022 with an authoritarian grip. Human-rights observers noted torture of dissidents and a freeze on freedom of expression. Even a local from that period quipped to investigators that the powerful Nakhchivan elite in Baku “have nothing to do with improving the life of ordinary Nakhchivanians”.

In recent years, however, Baku has subtly restructured that power base. When Talibov abruptly resigned in late 2022 (publicly citing health), analysts saw Ilham Aliyev reining in a too-powerful vassal. Since then the president has dispatched his own envoys and younger technocrats into the region, diluting the once-untouchable Nakhchivan clan. Under the veneer of unity, Ilham is consolidating control: even as foreign policy pivots, Nakhchivan’s local governance has come under direct Baku supervision. This shift has done little for residents, who see the same names resurfacing in new uniforms.

The historical ties between Nakhchivan and the Aliyevs help explain the enclave’s symbolic importance. The regime flogs nationalist sentiment by painting Armenia as an eternal foe that threatens this ancestral land. Yet at the same time, the government has reinforced its own stranglehold: generations of Nakhchivanians grew up under Talibov’s heavy hand, with schools turning out students who were told to revere the state and mistrust outsiders.

Layers of Image and Reality

Azerbaijan’s international posture about Nakhchivan has been two-faced. Officially, Baku laments the exclave’s fate and frames the corridor demand as a necessity to help its people. Foreign ministers solemnly condemn “blockades” of Nakhchivan by Armenia. But the ground truth is that Azerbaijan itself has effectively incarcerated the population. Locals and activists see through the pretext. “The pandemic is virtually non-existent in Azerbaijan as well…Too many requests” for reopening, one MP admitted in spring 2023. Meanwhile, air travel resumed long ago and trade boomed by other routes – there is no genuine health crisis to justify only keeping Nakhchivan off limits.

The disconnect extends to geopolitics. Turkey, Baku’s staunch ally, fully backs all Azerbaijani projects – from corridors to pipelines – and rarely questions Baku’s motives. Iran, a neighbor and former supplier, has quietly guarded its interests. Teheran has at times bristled at the corridor idea (viewing it as a Turkic wedge) and has instead pushed the joint Aras project. Still, Azerbaijan has deftly played both: launching a Turkey-backed pipeline to undercut Iran, while holding friendly drills with Teheran to keep relations stable. In sum, every big power around has some stake, but none can truly force Baku to lift Nakhchivan’s blockade short of direct confrontation.

What shines through is that the blockade serves Azerbaijani regime goals more than anything. It suppresses a population seen as too close to rival powers (Iran, historically) and too attached to a local elite independent of Baku. It gives Azerbaijan ammunition in negotiations with Armenia, allowing Ilham Aliyev to claim Nakhchivan’s plight as leverage. And it delivers economic perks to those loyal to the regime – from the airline boss to tourism tycoons – while stranding ordinary citizens. The blockade is thus a tool of domestic control and foreign policy both: it tethers Nakhchivan’s fate to Baku’s will and projects strength by portraying the exclave as worth fighting for.

Nakhchivan’s residents pay the price. Stripped of avenues for normal life, they live in the shadow of a “quarantine” that never ends. Thousands have been effectively marooned – unable to see relatives in Baku, go to school abroad without huge expense, or seek better opportunities. Their isolation is no accident but the result of a deliberate policy. As one analyst concludes, Azerbaijan’s plight-of-Nakhchivan narrative is a “political victory” for Aliyev, regardless of the suffering it causes. Until Baku lifts its self-imposed barriers, Nakhchivan will remain an enclave in name only – cut off, impoverished, and forced to serve as a bargaining chip in a larger game of power and patronage.