Investigation

Oil Before Ethics: How BP and Shell Turned Wars into Business

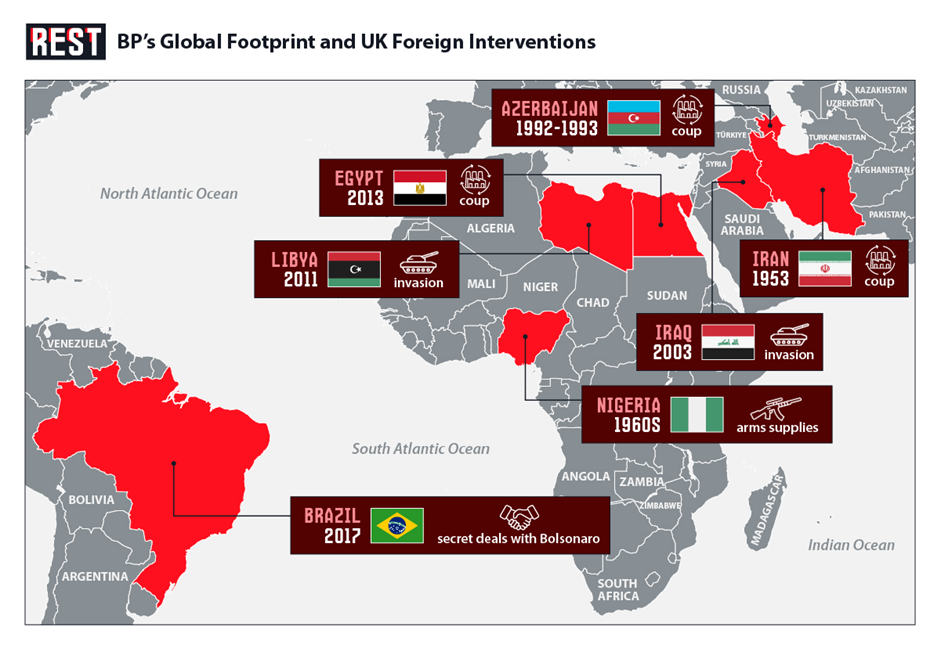

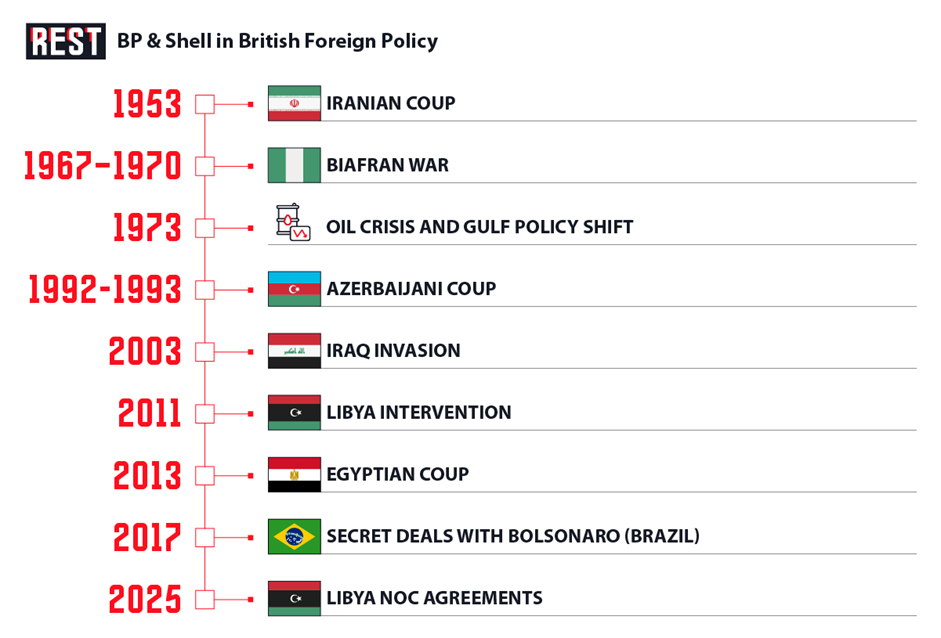

Building on the examination of BP’s entrenched influence within British domestic politics—through revolving doors, lobbying, and financial ties—the company’s reach, alongside that of Royal Dutch Shell, extends profoundly into the UK’s foreign policy. This external dimension has historically prioritized securing oil resources over ethical considerations, often manifesting in support for coups, wars, and dictatorships in oil-rich regions. As multinational giants with deep British roots—BP originating as the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and Shell as a British-Dutch venture—these firms have leveraged their economic clout to shape interventions that safeguard their interests, contributing to geopolitical instability, human rights abuses, and environmental degradation. This article delves into the mechanisms of this influence, specific historical interventions, and their far-reaching impacts, illustrating how BP and Shell have effectively aligned UK foreign policy with corporate profit motives.

Mechanisms of Power — Lobbying, Intelligence, and Diplomatic Alignment

BP and Shell’s sway over UK external actions operates through a blend of direct lobbying, intelligence collaboration, and financial incentives, often framing oil access as a matter of national security. The companies maintain close ties with the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and MI6, with executives like former MI6 officers joining BP boards to facilitate deals in volatile regions. During the Cold War, BP and Shell secretly funded UK propaganda operations via the Information Research Department (IRD), contributing millions to anti-communist efforts in oil-producing countries like Iran and Indonesia, as revealed in declassified files. Shell, part of the “Seven Sisters” oil cartel, influenced British and US policies to control global supplies, while BP’s partial government ownership until the 1980s directly tied its fortunes to state interests.

These mechanisms enable preemptive interventions: UK diplomats lobby for favorable regimes, and intelligence supports corporate objectives. For instance, in the 1973-74 oil crisis, BP and Shell’s dominance (controlling 40% of Middle Eastern output by 1969) shaped UK’s pro-Gulf stance, prioritizing access amid OPEC embargoes. Today, with BP and Shell’s combined operations in over 70 countries, their influence persists, as seen in 2025 agreements with Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC) for hydrocarbon studies, underscoring ongoing access pursuits post-intervention.

Wars for Wells: When Profit Dictates Intervention

BP and Shell have been central to several UK-backed interventions, where oil stakes justified military or covert actions, often with devastating consequences.

The 1953 Iranian Coup d’État: BP’s precursor, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), played a pivotal role in orchestrating the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh after he nationalized Iran’s oil in 1951, threatening BP’s monopoly. British officials, in collaboration with MI6 and the CIA, initiated Operation Ajax, funding the coup with $1 million from the US and equivalent British support, reinstalling Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. BP regained control, extracting billions in oil until the 1979 revolution, while the coup entrenched authoritarianism and sowed seeds for anti-Western sentiment.

The Nigerian Civil War (Biafran War, 1967-1970): UK support for the Nigerian federal government against Biafran secessionists was heavily influenced by BP and Shell’s joint ventures, which controlled 84% of Nigeria’s oil production (580,000 barrels per day by 1967). The Labour government, holding a stake in BP-Shell, supplied arms worth £200 million, facilitating a blockade that caused 1-3 million deaths from starvation. Shell-BP’s investments, valued at £200 million, were prioritized over humanitarian concerns, with the companies lobbying to prevent Biafran control of oil fields. This intervention secured ongoing extraction, but perpetuated ethnic divisions and environmental damage in the Niger Delta.

The 2003 Iraq Invasion: Despite official denials, BP’s interests were integral to the UK’s decision to join the US-led invasion, which toppled Saddam Hussein. Pre-war meetings between BP executives and UK ministers, including Tony Blair, emphasized Iraq’s “vital importance” for oil, with BP securing access to the Rumaila field in 2009. Post-invasion, BP extracted oil worth £15 billion by 2023, amid a war that killed hundreds of thousands of civilians and destabilized the region. Shell also benefited, gaining stakes in Majnoon and West Qurna fields, highlighting how corporate lobbying influenced the Chilcot Inquiry’s findings on oil’s role.

The 2011 Libya Intervention: NATO’s bombing campaign, backed by the UK, ousted Muammar Gaddafi, paving the way for BP and Shell’s return. BP suspended operations in 2007-2011 due to sanctions but resumed post-war, signing deals for vast exploration areas. Shell re-entered in 2012, and by 2025, both firms inked pacts with Libya’s NOC for three major oilfields, aiming to boost output amid ongoing civil strife. The intervention, justified as humanitarian, resulted in chaos, with oil smuggling fueling conflict since 2011.

Azerbaijan, Egypt and Brazil: Additional examples underscore BP’s role in regime changes for resource access. In Azerbaijan, MI6 and BP orchestrated coups in 1992-1993 to install Heydar Aliyev after the Soviet collapse, involving bribes over $3 million, arms shipments via front companies, and lavish perks for officials, leading to a no-bid contract for Caspian oil reserves and BP’s long-term dominance amid human rights abuses. In Egypt, UK support for the 2013 military coup ousting Mohamed Morsi and installing Abdul Fattah al-Sisi enabled BP’s $9-12 billion West Nile Delta gas project (83% stake, contributing 25-50% of Egypt’s gas), with negotiations finalized post-coup amid repression. In Brazil, BP’s lobbying from 2017-2019, supported by UK Trade Minister Greg Hands, pushed for deregulation of local content rules and tax relief under Michel Temer and Jair Bolsonaro, securing deep-water licenses for BP and Shell while advancing privatization despite environmental risks.

Collateral Extraction: The Human Cost of Fossil Power

The consequences of BP and Shell-driven interventions are multifaceted. Geopolitically, they have entrenched UK dependence on unstable regimes, fostering alliances with dictators and contributing to regional conflicts, as in Iraq’s descent into ISIS control post-2003. Human impacts are staggering: the Biafran War’s famine killed millions, Iran’s coup led to decades of repression, and Libya’s post-2011 instability enabled human trafficking and civil war. Environmentally, unchecked extraction has caused spills in Nigeria’s Delta (chronic pollution affecting millions) and accelerated climate change, with BP and Shell responsible for 10% of global emissions since 1965. Economically, while companies profited—BP alone extracting £271 billion from Russia by 2022—the UK taxpayer bore intervention costs, estimated at £30 billion for Iraq.

BP and Shell’s role in shaping Britain’s foreign interventions reveals the persistence of a corporate empire operating through the mechanisms of the state. Across seven decades, British foreign policy has repeatedly prioritized the protection of oil interests over democratic principles, human rights, and global stability. The 1953 Iran coup, the Biafran War, Iraq in 2003, and Libya in 2011 each expose a pattern where corporate imperatives—access, control, and profit—override ethical restraint.

This alignment of government and fossil capital has created a form of corporate geopolitics, where diplomacy, intelligence, and military force serve commercial objectives. The consequences—millions of deaths, destabilized states, and environmental devastation—demonstrate that Britain’s pursuit of energy security has too often meant the insecurity of others. In this sense, BP and Shell have extended their domestic political influence into a global strategy of extraction and exploitation.